PERU´S PRESIDENT PEDRO PABLO THE BRIEF / THE ECONOMIST

Bello

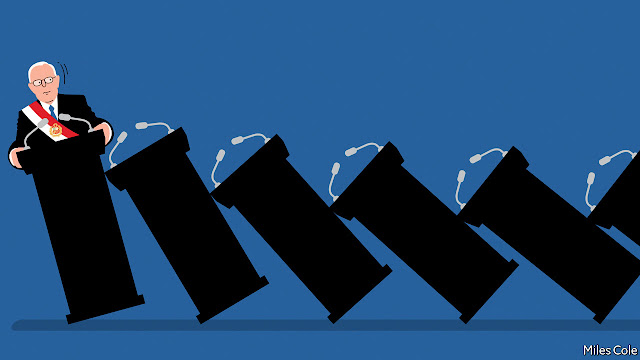

Peru’s President Pedro Pablo the Brief

Lessons from another fallen leader

EVER since it began in July 2016 the presidency of Pedro Pablo Kuczynski in Peru looked like an accident waiting to happen. He squeaked into a run-off election only after his supporters in Peru’s media and business establishment helped to press the electoral authority to disqualify a more popular rival, Julio Guzmán. After he unexpectedly defeated Keiko Fujimori, a conservative populist, in the run-off by just 0.2% of the vote, she exercised her pique by using the congressional majority gained by her Popular Force (FP) party to harass Mr Kuczynski’s government. After narrowly surviving one impeachment attempt in December last year, PPK (as Peruvians know him) resigned on March 21st when defeat in another became inevitable. Having served just 20 months, he became the 19th elected president in Latin America in the past 30 years to fail to complete his term.

Many of these were victims of the instability inherent in Latin America’s unique combination of directly elected presidents and legislatures chosen by proportional representation. This arrangement means that presidents often lack congressional majorities. In PPK’s case, there were two aggravating factors. The presence of a host of small parties meant that the electoral system rewarded FP with 73 of the 130 seats in the unicameral congress, although it won just 36% of the vote. And Peru’s constitution, unusually for Latin America, contains parliamentary elements: congress can oust ministers and cabinets almost at will, and proceeded to do so.

Any president would have been tested by such a spiteful and powerful opponent as Ms Fujimori. But PPK played a big part in his own downfall. Although he had served in past governments, for most of his life he worked as an economist and businessman. He showed a disastrous disdain for politics. He appointed cabinets in his own image, stuffed with technocrats and business people. Friendship with the president outweighed knowledge of ministerial briefs or of a large and socially diverse country. A clearer political and communications strategy might have kept public opinion on his side and thwarted Ms Fujimori. As it was, his government soon seemed rudderless and impotent.

Faced with impeachment, his response was a caricature of political bargaining. He struck a secret deal with Kenji Fujimori, Keiko’s estranged brother, who was an FP congressman, to pardon their father, Alberto, a former president jailed for human-rights abuses. The pardon was controversial. PPK gained the votes of Kenji’s nine followers in congress, but he lost more: the backing of part of the left, of some of his own legislators and of many voters. Kenji was an ally of dubious worth. The release of clandestine videos of him and his allies offering FP legislators bribes in the form of public contracts made PPK’s defeat in a second impeachment certain.

It was PPK’s failure to distinguish between private business interests and public responsibility that had rendered him vulnerable to impeachment in the first place. Companies that he owned or to which he was linked earned $4.8m in fees from Odebrecht for consultancy work, some awarded when PPK was a minister in 2001-06 and signed a big public contract granted to the Brazilian construction company. This may have been legal, but it was unethical. That politics matters, that technocracy alone is not enough and that public servants must be seen to avoid conflicts of interest are lessons that appear to have been learned by two more successful businessmen-turned-presidents, Argentina’s Mauricio Macri and Sebastián Piñera of Chile, but not by PPK.

As for Peru, it may gain a respite under Martín Vizcarra, PPK’s vice-president, who has taken over the top job. A former provincial governor who belongs to no party, he has a record as a negotiator. FP may give him an easier ride, at least until after local elections in October. Ms Fujimori is facing an investigation over a claim by Odebrecht (which she denies) that it gave her campaign money in 2011.

For much of this century, Peru has been an economic success. But Peruvians are rightly disillusioned with their politicians. Four of the five living elected presidents have been accused of corruption. Growth has fallen to around 3% a year. Reviving it requires institutional reforms, especially of local government, education, the judiciary and the political system. The fujimoristas have blocked them. The fact that they are divided and in disarray offers an opportunity. Understandably, Mr Vizcarra’s instinct may be to play safe. But his best hope of surviving until 2021 is to be ambitious, and to set out a bold programme for a better country that Peruvians can rally around.

0 comments:

Publicar un comentario