What Does the End of The Liberal International Order Mean for Markets?

By John Mauldin

“Globalization [has] overshot and produced a quite legitimate backlash. While people like me were enjoying Davos and Aspen and saying how marvelous the Liberal International Order was, a rather large number of ordinary Americans were not feeling quite so chipper.”

—Niall Ferguson

“Niall Ferguson is not the kind of historian who suffers from understatement. He writes big, muscular books with high-concept ideas that target current concerns through the prism of the past. They are pull-yourself-together warnings to the present by way of arresting historical precedent.”

—The Guardian

If there is a sentence (or two) that encapsulates my thoughts on globalization, it is the William Gibson quote I’ve used many times at the opening of my letters: “The future is already here. It’s just not evenly distributed yet.”

The benefits of globalization have been unevenly distributed, and those who have been on the short end of the curve are pushing back. Given the dire situation millions of Americans are in today, I don’t wonder why they are doing so; I wonder what took them so long.

According to a 2017 study by the Federal Reserve, 44% of Americans wouldn’t be able to cover an unexpected $400 expense without borrowing or selling something. Yes, nearly half the country can’t come up with $400 cash in an emergency. That’s stunning. The slightest mishap—a toothache, a minor car problem—will send them into debt or force them to sell something.

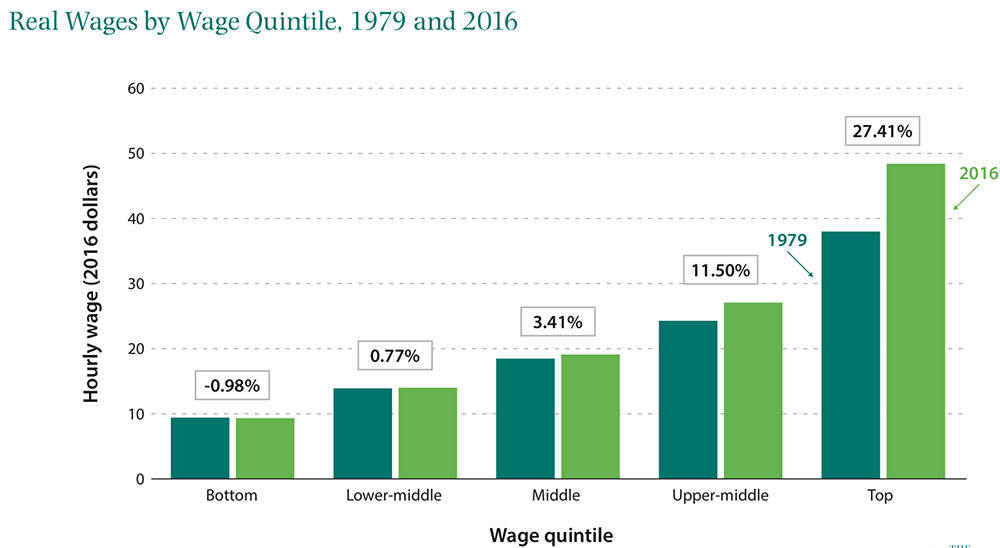

This situation is the result of decades of stagnant wage growth. Since 1979, real (inflation-adjusted) hourly wages for the bottom quintile of earners fell by 1%. Worse, the inflation adjustment is based on the CPI, which as I’ve said many times, understates the real cost of living for most people. But wages haven’t stagnated for everybody. As the below chart shows, real hourly wages for the top quintile of earners have increased by over 27% in the same period.

Source: Brookings Institute

Over the past four decades, globalization has enabled the transfer of millions of jobs from the US to various emerging-market countries. It changed the relative value of capital and labor all over the world. The top earners started getting a larger share of their income from investments than from their labor. They own the “means of production,” and the producers did increasingly well from the ’70s forward.

Nobody paid much attention to the unevenly distributed benefits of globalization, until around 40 million Americans lost their jobs in the 2007–2009 recession. Now, the backlash has begun, and it’s not going to stop until the situation improves for those who have been left behind.

Globalization has lost its political support, and that raises an important question about the future of the global economy. If globalization has fallen out of favor with large swaths of the voting public, what does the future look like for the American-led order which has promoted economic liberalization and liberal values around the world since the end of WWII?

This system, defined as the Liberal International Order, is the framework of rules, alliances, and institutions that is credited with the relative peace and prosperity the world has enjoyed since 1945.

So, if the order has lost support, will the world plunge into beggar-thy-neighbor protectionism?

Worse, without the threat of military intervention by the US and its allies, will regional powers start to challenge one another?

One man answering these pressing questions is my good friend, Niall Ferguson. I’m sure most of you have heard of Niall, but for those who haven’t, it is my great pleasure to introduce him to you.

Niall Ferguson is a senior fellow at Stanford University, and a senior fellow of the Center for European Studies at Harvard, where he served for twelve years as a professor of history. Niall is one of the finest economic historians on the planet; but he isn’t only an academic. What many people don’t know is that he works with a small group of elite hedge fund managers and executives as the managing director of macroeconomic and geopolitical advisory firm, Greenmantle.

Niall has made a habit of tackling topics that have significant importance in his career. But in my opinion, this is the most critical question Niall is attempting to answer: “Is the Liberal International Order over?”

Before we dive in, I want to make clear that the goal of this letter is not to say whether liberal internationalism is good or bad, or defend the backlash against it. My objective is to highlight the current state of the order and give insight into Niall’s argument behind why he believes it is over. As investors, it is imperative we understand this trend because it has major implications for financial markets we need to think about. With that being said, let’s dive straight in.

The fate of the Liberal International Order rests on Pax Americana

In a recent interview, Niall pointed out the potentially fatal flaw in the Liberal International Order:

“If the world has been more peaceful since WWII, the main reason is not because of the Liberal International Order, it’s because the United States had decided to play a leadership role. The big story after 1945 was the Pax Americana. The big story since 9/11 has been its crumbling.”While the Liberal International Order and its institutions are credited with the relative peace the world has enjoyed since 1945, Niall says, “That's a very implausible argument.” He believes the world has been more peaceful because of the will and capacity of the US to be the principal guarantor of the system. This is often referred to as Pax Americana, in which the US employed its overwhelming military power to shape and direct global events.

This reliance on US strength hasn’t been a problem for the past seven decades, but times are changing. Since the financial crisis, the US has been less willing to bear the costs needed to be the guarantor of the international order. Niall highlights the inaction over Russia’s annexation of Crimea in 2014, and the “little more than cosmetic” strikes against Syria as signs that the US is starting to take a more ambivalent approach to global conflicts.

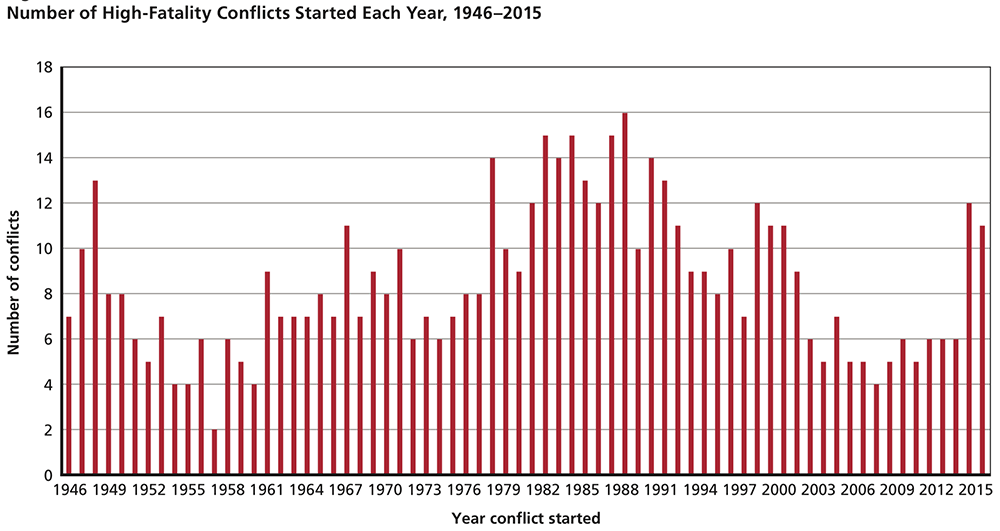

Without US willingness to use military power to establish balance across the world, it’s likely the liberal order will buckle under the unrestrained competition of regional powers. As the below chart shows, there has already been a sharp rise in the number of armed conflicts around the world.

Source: RAND Corporation

As Niall pointed out: “Things are becoming quite disorderly for the liberal order.” Before we go on, I want to make a critical point. Whether you support military intervention, or not, isn’t the issue here.

The issue is that without the US playing the role of guarantor, we are likely to see a rise in conflicts.

That is going to affect financial markets and your portfolio.

The second “pillar” of the Liberal International Order, economic liberalization, is also under strain.

Peak globalization is in the rearview mirror.

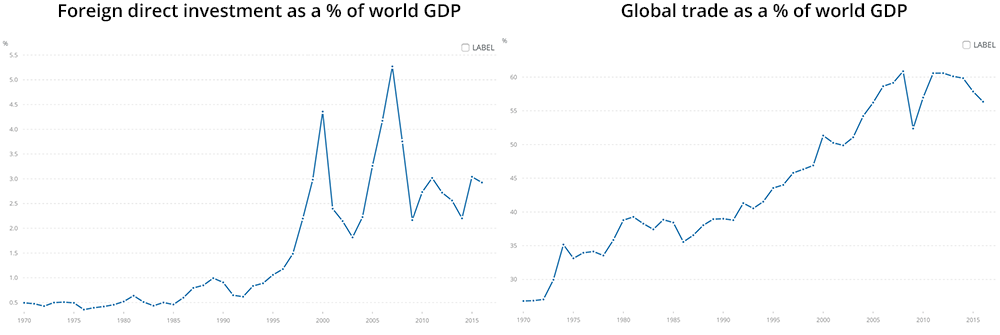

Niall points to falling global trade and capital flows as another symptom of the Liberal International Order being over:

“Peak globalization is already behind us. Trade is no longer growing at the rate it did prior to the financial crisis, and international capital flows have fallen too.”Since peaking in 2007 and 2008, respectively, trade and foreign direct investment as a percentage of world GDP have fallen sharply. McKinsey Global Institute found that global flows of goods, finances, and services have declined by 15% since peaking in 2007.

Source: World Bank

I believe “peak globalization” is in the rearview mirror. I say that not only because cross-border flows have declined precipitously, but because we are headed into a period of protectionism. US withdrawal from the Trans-Pacific Partnership is the most high-profile instance so far, but there are several more.

The governments of Australia and Canada have taken measures to curb foreign ownership of real estate. New Zealand has taken this a step further by outright banning foreign ownership of real estate.

In Europe, there have been several “behind the border” restrictions enacted by countries, which are designed to bolster domestic industries. Thus, it seems to me even the most liberal of countries are realizing globalization has overshot.

The rise of protectionism has serious implications for investors. We have become used to companies being able to break into new markets and the idea of “multinational corporations.”

This may not be the case going forward. Investors will have to pay a lot more attention to where the companies they choose to invest in operate, and where their sales come from. In short, protectionism is on the rise and investors must prepare accordingly.

Longtime readers will know that I’m second to no one in defending free trade—but I also see the reality, which is that it has had a dark side. And that dark side is another symptom Niall has pointed to as proof that the International Liberal Order is over.

Globalization has killed the goose that lays the golden eggs

Although the Liberal International Order has benefited some, Niall points out that it has been very bad for millions of ordinary Americans:

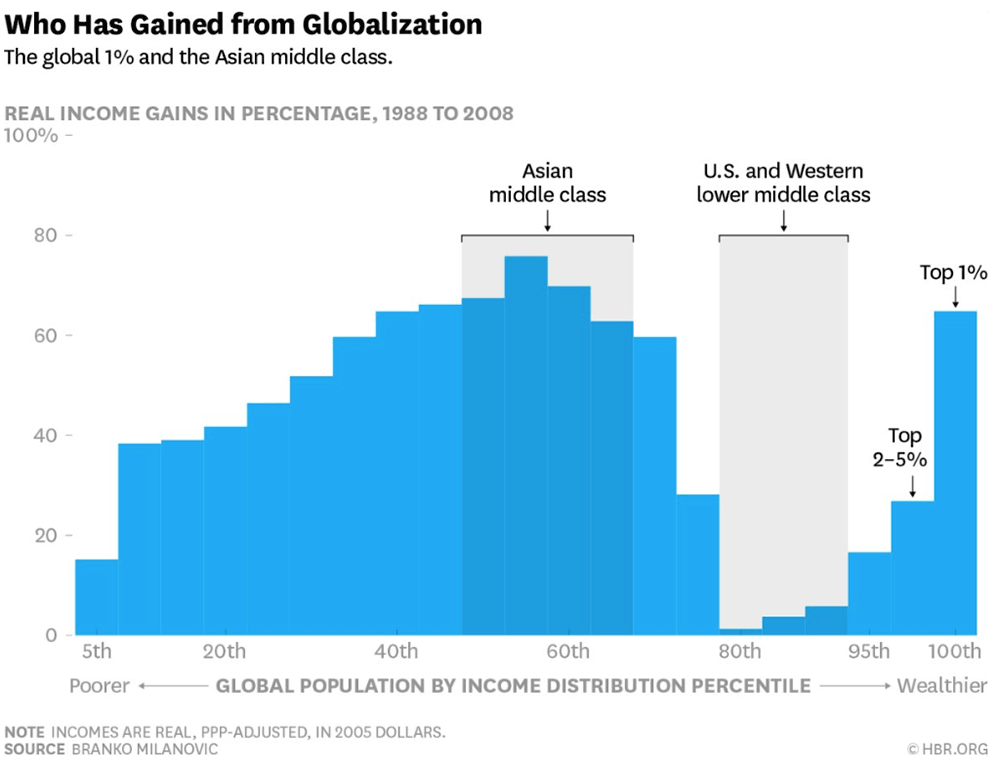

“While it's great to say that 300 million Chinese people have been pulled out of poverty, the reality is that there has been, at the same time, a significant erosion of living standards for middle-class and working-class Americans.”I mentioned at the beginning of this letter that the benefits of globalization have been unevenly distributed. As the below chart shows, the big losers have been the American middle and working classes.

Source: Harvard Business Review

Globalization has been bad for these sections of society because it changed the relative value of capital and labor. When capital and goods could flow freely between the US and emerging market countries, the value of labor in the US fell dramatically. Today, we are at a point where labor share of income has fallen to an all-time low of 57%. That means a growing fraction of the gains have been going to capital, and those who have it.

This has resulted in the loss of millions of US jobs. Since 1979, manufacturing employment has dropped by approximately seven million jobs. Studies show that technology accounts for around half of these losses. But Niall makes a very succinct point about these findings:

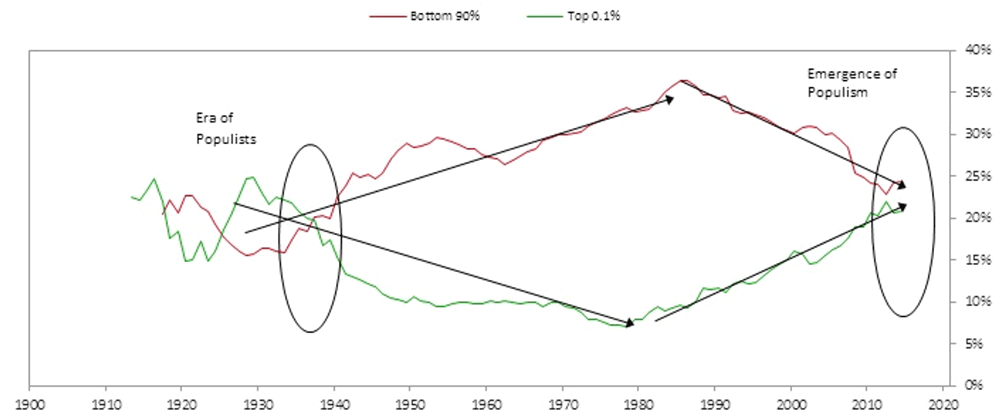

“The distinction [between globalization and technology] is arbitrary. What distinguishes the technological revolution is precisely that things like iPhones could be designed in California but made in China. The paradox of the Liberal International Order is that it made a lot of technology affordable, while at the same time destroying manufacturing jobs.”The hardship experienced by millions of Americans has happened at a time when the wealthy have done increasingly well. Today, we have a situation where the top 0.1% of the population has roughly the same share of the US national wealth as the bottom 90%. Cue: the re-emergence of populism.

Source: Ray Dalio, Bridgewater Associates

Two very different presidents, but both responsive to the most intensely angered voters of their eras.

You only have to observe how the word “globalist” has become a slur to see that people have turned against liberal internationalism and those who support it. Globalization has been terrible for millions of middle- and working-class Americans, and they are very unlikely to vote for politicians who support it. By lowering the living standards for millions of Americans, the Liberal International Order has become the architect of their own downfall.

Niall has also highlighted events taking place on the other side of the Atlantic as another sign that the Liberal International Order is indeed finished.

The European Union has a crisis of confidence

Niall says the EU’s mishandling of the financial and migrant crises have resulted in a total loss of confidence in the institution:

“The European Union is a perfect illustration of why the Liberal International Order is over. The EU wholly mismanaged the financial crisis, massively amplifying the effects on member states. But it will turn out to have committed suicide because its leaders got the immigration issue wrong. The Europeans forgot that borders are really the first defining characteristic of a state. As they became borderless, they made themselves open to a catastrophe, which was the uncontrolled influx of more than a million people. The most basic roles that we expect a state to perform, from economic management to the defense of borders, were flunked completely by the EU over the past 10 years.”The EU’s incompetence in both situations has ignited a wave of populism across the continent:

- Austria elected a 31-year-old, anti-immigration candidate as Chancellor.

- Italy’s populist Five-Star movement are leading in the polls for the general election, which takes place March 4.

- The Visegrad group, which consists of the governments of Poland, Hungary, Czech Republic, and Slovakia, have strongly opposed the resettlement of refugees and are battling with the EU over the issue.

- Angela Merkel did win the German elections, but four months later, she hasn’t been able to form a government because of the strong showing by the populist Alternative for Germany party.

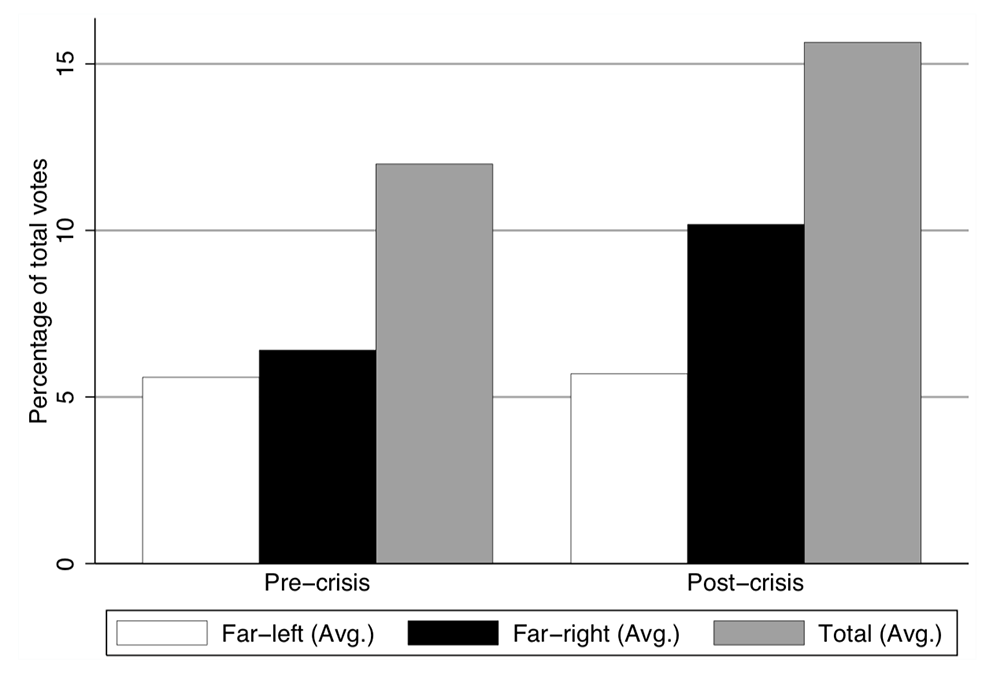

This populist backlash shouldn’t come as a surprise to us. During a recent discussion, Niall pointed out that: “If one looks at all the elections back to 1870, financial crises lead to backlashes against globalization that erode to the political center.” Here’s a chart which shows this trend:

Source: Funke, Schularick, Trebesch (2015)

This is why I love talking with Niall. He makes sense of current trends by providing a historical perspective. Getting Niall’s insight not only allows you to understand what is currently happening, but how things are likely to unfold in the future.

While the EU’s handling of the financial crisis hasn’t been good for business, I believe their mismanagement of the migrant crisis will prove to be their real downfall. According to Frontex, the EU border surveillance agency, over the course of 2015 and 2016, more than 2.3 million illegal crossings into Europe were detected. This influx of migrants hasn’t gone unnoticed.

A recent survey by Paris-based think-tank, Fondapol, found that nearly two-thirds of EU citizens surveyed believe immigration has a negative impact on their countries. As the below chart shows, a similar percentage of respondents said they are “very worried/worried” about Islam.

Source: Fondapol, Financial Times

Despite the concerns of people all across Europe about immigration, EU officials continue to push refugee resettlement on member states. The EU’s actions in the face of these concerns proves that there is a complete disconnect between those in Brussels and ordinary Europeans.

I can’t see how this doesn’t cause a further increase in support for populism around Europe, and ultimately lead to the demise of the EU—which would certainly prove that the Liberal International Order is over. To be clear, I don’t think the collapse of the EU is imminent, but it is certainty on a downward trajectory.

We saw this movie before, will it have the same ending?

As I mentioned, Niall has a special ability to dissect historical trends and extrapolate out what they can tell us about the future. He did this recently with the Liberal International Order:

“The big lesson of history is that we have run the experiment of hyper-globalization before. In the late 19th century, many of the forces we are seeing [today] were at work: International migration reached levels we have begun to see again, the percentage of the US population that was foreign born reached 14%, and free trade and international capital flows reached new heights. At the time, the 1% were tremendously happy. Unfortunately, they underestimated the backlash that happens when globalization runs too far. The populist backlash [in the late 19th century] was just the beginning of a succession of crises that culminated in 1914 with WWI. War can be global too, and we will know the Liberal International Order has failed when it does what the last one did, and that is to produce a major conflict.”I’m not sure if the Liberal International Order will end in war, but the current state of affairs can’t last much longer. Globalization has jumped the shark, and as a result, we are seeing a powerful backlash from those who have been hurt by it. There is no way to predict how this situation will unfold. But I know that I want to be the first to hear about any developments, because they have serious implications for financial markets and the societies we live in.

I have so many questions I want to ask Niall about this trend and many others. That’s why I’ve invited him back to give a keynote speech at my Strategic Investment Conference in San Diego this March.

Niall last spoke at my conference two years ago. He was bullish on the global economy at a time when almost everybody—including me—was bearish. I really don’t know what Niall is thinking about right now, or what new insights he has in store for SIC attendees. I am truly excited to welcome him back and I hope you can be there with me to experience it, first-hand. If you would like to learn more about attending the SIC 2018, and about the other speakers who will be there, you can do so here.

“I told my sister about the conference and why I was going. She said, "Of course! Not going would be like standing around and missing 1968 in San Francisco."

—C. Cayes (past SIC attendee)

That concludes the fifth and final installment in this series. I hope you have enjoyed reading my insights into these “big ideas” as much as I have enjoyed writing them. Although it’s over, I do have something special to send you in the coming days. It’s a personal video message that I just finished recording. Think of it as a stepping stone to taking these “big ideas” to the next level.

I’ll tell you more about it in my series recap email, tomorrow.

John Mauldin

Chairman

0 comments:

Publicar un comentario