Swiss prepare to vote on corporate tax unification

Reforms to sweep away attractive deals for multinationals head for referéndum

by: Ralph Atkins in Geneva

It is not only Geneva’s lakeside setting that multinational companies find idyllic.

Switzerland has a long history of offering preferential fiscal terms to international investors, and low tax rates have helped to attract companies such as Caterpillar and Japan Tobacco.

But the country faces a huge challenge if it wants to retain those companies. Under international pressure, voters are being asked in a national referendum next Sunday to approve reforms that would sweep away selective tax deals and introduce unified low rates for all companies.

The vote is on a knife-edge. Supporters of reform say Switzerland cannot afford to be so generous. But rejection could prompt other countries to retaliate for the continued tax breaks, creating economic uncertainty and instability.

“It is very important for Geneva,” says Serge Dal Busco, the canton’s finance minister, who backs the reforms. “Some 62,000 jobs in the canton rely directly or indirectly on multinationals.

If they don’t have a favourable tax environment, we could lose at least some of those jobs.”

Switzerland, one of the most affluent countries, has had to rethink its economic model during the past decade. US-led legal action against banks that helped overseas clients to evade taxes has led to greater transparency in the financial system.

Threats of retaliatory action by trading partners led Bern to agree to corporate tax norms set by the EU, with which it has vital business links, and the Paris-based OECD.

“The Swiss government had to recognise that instruments which worked well for many years could no longer be used,” says Peter Uebelhart, head of tax at KPMG Switzerland.

The reputation for being attractive to business started after the second world war. Switzerland gave international companies special status, with cantons competing to offer the best tax breaks.

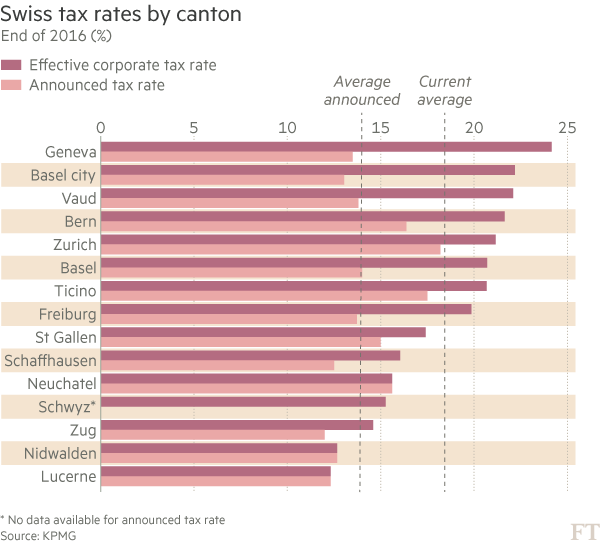

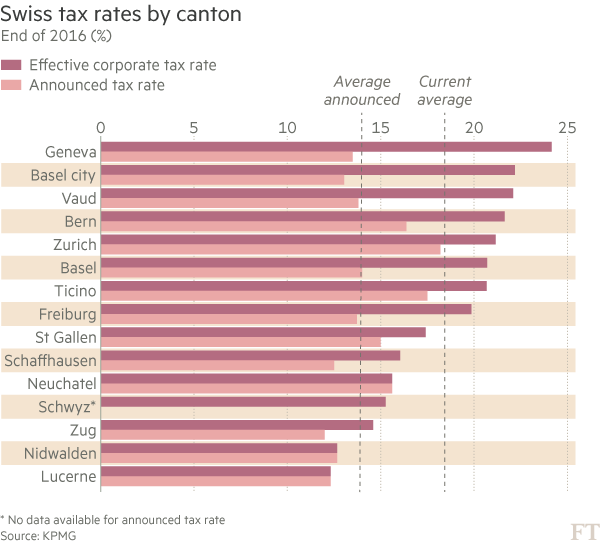

Multinationals with “auxiliary status” in Geneva pay an average corporate tax rate of 11.6 per cent, compared with the 24.16 per cent for ordinary businesses, one of the highest rates in Switzerland.

Under the proposed reforms international and domestic companies would pay the same rates. Rather than multinationals paying significantly more, cantons would slash standard corporate tax rates.

Geneva’s main corporate tax rate would almost halve to 13.49 per cent.

Business wants the referendum to pass. “Keeping the jobs, keeping the companies — that is what is at stake,” says Blaise Matthey, director-general of the Federation of Romandy Business, which represents companies in the French-speaking part of Switzerland, including Geneva.

“We are rethinking our economic model and it is changing quite rapidly. People complain but there is no choice. If you don’t abide by international standards, you get put on a blacklist.”

Although the federal government has promised to help the cantons to bridge any revenue shortfalls from the unified lower rate, the implications for local budgets alarm opponents.

“The reforms will cost much more than the [federal] parliament thinks,” says Sandrine Salerno, Social Democratic finance director in the Geneva city government. “For sure the level of tax is important for companies, but it is not the only reason why they come to Geneva and Switzerland. They also come because of the good quality infrastructure — the schools and safety, for instance.”

Fuelling voter suspicion is the complexity of the reforms, which opponents argue will line the pockets of tax advisers and lawyers. The new system would introduce an internationally approved “tool box” of tax relief measures that cantons could offer companies. These would include incentives for research and development, relief for income from patents and tax breaks on shareholders’ equity.

Supporters of the reforms point out that while multinationals will face slightly higher rates, for ordinary companies tax bills will be much lower. That could stimulate investment and job creation, which in time would boost cantons’ coffers, though the impact is hard to predict.

Geneva scores highly for its qualified workforce and transport connections, says Jan Schüpbach, economist at Credit Suisse. The tax reforms would remove “its main disadvantage — a relatively high corporate rate”.

Opponents say the package could easily be made more acceptable. “Everyone agrees on the main principle that all companies should pay the same tax rates,” says Ms Salerno.

But those who worked on the proposals say they took years to negotiate and finally balance Switzerland’s attractiveness as a business location with international requirements and pressures on public finances. “This is the best possible package you could have within the limits,” says Mr Uebelhart.

Mr Matthey says: “Multinationals want a stable tax framework, they want a solution that is agreed with the EU . . . If we can’t do this, they will leave, because you can’t do business in an unstable environment.”

Switzerland has a long history of offering preferential fiscal terms to international investors, and low tax rates have helped to attract companies such as Caterpillar and Japan Tobacco.

But the country faces a huge challenge if it wants to retain those companies. Under international pressure, voters are being asked in a national referendum next Sunday to approve reforms that would sweep away selective tax deals and introduce unified low rates for all companies.

The vote is on a knife-edge. Supporters of reform say Switzerland cannot afford to be so generous. But rejection could prompt other countries to retaliate for the continued tax breaks, creating economic uncertainty and instability.

“It is very important for Geneva,” says Serge Dal Busco, the canton’s finance minister, who backs the reforms. “Some 62,000 jobs in the canton rely directly or indirectly on multinationals.

If they don’t have a favourable tax environment, we could lose at least some of those jobs.”

Switzerland, one of the most affluent countries, has had to rethink its economic model during the past decade. US-led legal action against banks that helped overseas clients to evade taxes has led to greater transparency in the financial system.

Threats of retaliatory action by trading partners led Bern to agree to corporate tax norms set by the EU, with which it has vital business links, and the Paris-based OECD.

“The Swiss government had to recognise that instruments which worked well for many years could no longer be used,” says Peter Uebelhart, head of tax at KPMG Switzerland.

The reputation for being attractive to business started after the second world war. Switzerland gave international companies special status, with cantons competing to offer the best tax breaks.

Multinationals with “auxiliary status” in Geneva pay an average corporate tax rate of 11.6 per cent, compared with the 24.16 per cent for ordinary businesses, one of the highest rates in Switzerland.

Under the proposed reforms international and domestic companies would pay the same rates. Rather than multinationals paying significantly more, cantons would slash standard corporate tax rates.

Geneva’s main corporate tax rate would almost halve to 13.49 per cent.

Business wants the referendum to pass. “Keeping the jobs, keeping the companies — that is what is at stake,” says Blaise Matthey, director-general of the Federation of Romandy Business, which represents companies in the French-speaking part of Switzerland, including Geneva.

“We are rethinking our economic model and it is changing quite rapidly. People complain but there is no choice. If you don’t abide by international standards, you get put on a blacklist.”

Although the federal government has promised to help the cantons to bridge any revenue shortfalls from the unified lower rate, the implications for local budgets alarm opponents.

“The reforms will cost much more than the [federal] parliament thinks,” says Sandrine Salerno, Social Democratic finance director in the Geneva city government. “For sure the level of tax is important for companies, but it is not the only reason why they come to Geneva and Switzerland. They also come because of the good quality infrastructure — the schools and safety, for instance.”

Fuelling voter suspicion is the complexity of the reforms, which opponents argue will line the pockets of tax advisers and lawyers. The new system would introduce an internationally approved “tool box” of tax relief measures that cantons could offer companies. These would include incentives for research and development, relief for income from patents and tax breaks on shareholders’ equity.

Supporters of the reforms point out that while multinationals will face slightly higher rates, for ordinary companies tax bills will be much lower. That could stimulate investment and job creation, which in time would boost cantons’ coffers, though the impact is hard to predict.

Geneva scores highly for its qualified workforce and transport connections, says Jan Schüpbach, economist at Credit Suisse. The tax reforms would remove “its main disadvantage — a relatively high corporate rate”.

Opponents say the package could easily be made more acceptable. “Everyone agrees on the main principle that all companies should pay the same tax rates,” says Ms Salerno.

But those who worked on the proposals say they took years to negotiate and finally balance Switzerland’s attractiveness as a business location with international requirements and pressures on public finances. “This is the best possible package you could have within the limits,” says Mr Uebelhart.

Mr Matthey says: “Multinationals want a stable tax framework, they want a solution that is agreed with the EU . . . If we can’t do this, they will leave, because you can’t do business in an unstable environment.”

0 comments:

Publicar un comentario