North Korea’s nuclear weapons

Another bombshell

After Pyongyang’s fourth nuclear test, China must change its tune towards its outrageous ally

. .

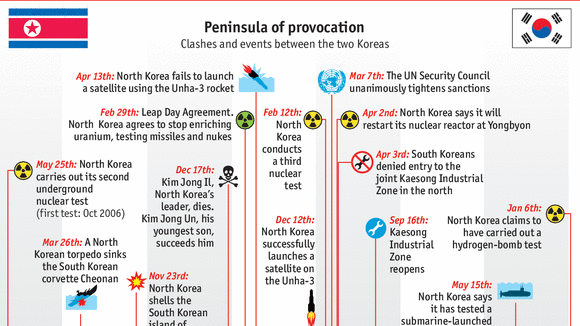

THE declaration on January 6th that North Korea had detonated its first hydrogen bomb was met with a show of joy on the streets of Pyongyang, its capital, and with despair in most others.

America, Japan, South Korea and even China protested. Outsiders picked up the magnitude-5 earthquake caused by the blast, and put its epicentre at Punggye-ri, site of an underground complex in the north-east, near China, where three previous tests, in 2006, 2009 and 2013, took place.

A fourth nuclear test had been expected. But most experts dismiss the claim that this was a hydrogen bomb of the sort found in advanced nuclear arsenals. Thermonuclear weapons, far more powerful than the atomic kind, are almost certainly beyond the North’s know-how. The explosion was roughly as big as the atom bomb detonated in 2013; even a failed detonation of an H-bomb would be more powerful. At a push, the North may have tested a “boosted-fission” weapon that uses a fusion additive to achieve a bigger bang. If so, it would mark a next step in the North’s nuclear programme—and a serious one.

Come on, China, change North Korea

The UN Security Council rushed to meet this week, condemning the test. Prodded by America, it is expected to pass a resolution calling for a fresh round of sanctions. Many will think this is just for show. After all, earlier sanctions following tests have hardly deterred a regime that seems set on possessing nuclear weapons. Indeed, they have allowed the Kim regime to claim that North Korea needs nukes to defend itself against enemies, led by America, that are bent on its destruction. The North’s state news agency said this week that the test had “guaranteed the eternal future of the nation”.

When dealing with North Korea, it is easy to despair. Dramatic remedies, such as trying to remove Mr Kim by force, are off the table because the risk is too great. Barely 50 kilometres from North Korea, 25m South Koreans live in greater Seoul, one of Asia’s most dynamic megalopolises. On the other side of the border are 1m North Korean troops and countless artillery pieces, with which the North has threatened to turn the southern capital into a “sea of fire”.

Even so, fresh sanctions should be just the start in confronting North Korea’s nuclear-tipped threats.

Not enough has been done to stem the flow of hard currency to a regime that even uses its diplomats to ferry illicit cash to Pyongyang. Financial sanctions can be made to bite deeper by more closely monitoring banking transactions. And the Vienna convention should not give cover to envoys engaged in criminality.

.

Under Barack Obama, America has let its North Korea policy drift. But the country that can do most is North Korea’s big neighbour and supposed friend, China. Its banks are the main conduit for North Korean money. More worryingly, China does next to nothing to stop the flow of nuclear technology between rogue states and North Korea. China’s sway over its neighbour is sometimes exaggerated, yet it is an economic lifeline, providing the regime with aid and trade. China is unhappy at the prospect of a nuclear-armed North Korea; but it is even more worried that the regime might collapse, possibly leading to a takeover by South Korea and America and the flight of millions of desperate North Koreans across its border.

Ideally, China would abandon the murderous Mr Kim. But even if it is unwilling to go that far, it can use the billions in aid and subsidised trade that it gives North Korea to press change upon the young dictator. Some may argue that squeezing the subsidies could hurt the poor, many of whom go hungry; it would also undermine the country’s budding class of private traders and entrepreneurs, who are its best hope for the future. But the aid and subsidised trade it has extracted have mainly enriched the Pyongyang elite and financed the nuclear programme. They would be the main victims of Chinese pressure—especially if the elite could no longer travel to China.

For decades North Korea has been adept at shaking down outsiders: first the Soviet Union, sometimes America and now China. Before it is too late, Beijing should stop subsidising a vile dynasty that gives nothing but headaches in return.

0 comments:

Publicar un comentario