The Gig Economy Is the New Normal

By John Mauldin

An already-confusing employment environment grew even more complicated this past week. Many readers responded to my “Crime in the Jobs Report” letter with their own stories. Some confirmed what I wrote, while others disputed it. Some of the stories I read from readers who are stuck far from where they want to be in this job market were very moving. I think everyone agrees the labor outlook is uncertain. I sense a lot of nervousness, even from those who have secure jobs that pay well. In today’s letter, I’m going to respond to some of the observations and data that came in this week on employment.

As we will see, we have a right to be nervous. Big changes in the employment world are happening, and we don’t yet know how they will affect us individually. Analysts like me can say we’ll muddle through, but we must remember that not everyone will muddle at the same pace.

We will also take a look today at a growing new phenomenon: the gig economy. (I should note that today’s letter is a little shorter. I am trying to reduce the word length of Thoughts from the Frontline.)

We talked last week about employers’ reluctance to hire older workers. Reader Steve Lange from Denver pointed me to a ZeroHedge article that questions this premise.

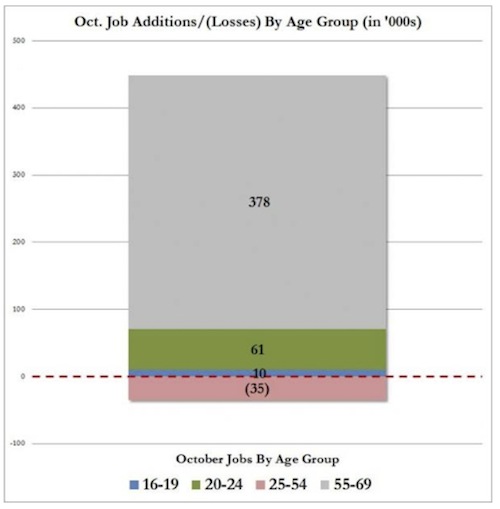

If you look at the BLS age breakdown for new jobs (Table A-9), you’ll see that workers aged 55 and over accounted for virtually all of October’s strong gains. That group added 378,000 jobs last month.

Meanwhile, the number of workers aged 25-54 actually declined by 35,000. That’s supposed to be “prime working age,” so any decline should ring alarm bells. And the numbers are more alarming if you are male: men aged 25-54 lost 119,000 jobs in October.

This pattern isn’t new, either. I’ve written about this ongoing anomaly in previous letters. Since December 2007, workers aged 55 and older have gained over 7.5 million jobs, while those under 55 have lost a cumulative 4.6 million jobs. Older workers are simply taking employment market share from younger workers.

What would cause this trend? Partly it’s demographic. The population is aging as the Baby Boomer bulge grows older and Millennials postpone parenthood. Nevertheless, it does look as though Baby Boomers are not exiting the labor force as fast as we thought.

Some Boomers may delay retirement simply because they enjoy working and are healthier than previous generations were in their late 60s. I’m in that category myself. More ominously, it seems that millions of Boomers are reaching retirement age without much in the way of retirement assets. They don't retire because they can’t afford to do so.

Tyler Durden, the pseudonymous ZeroHedge writer, connects this pattern to the unimpressive wage growth we’ve seen in this recovery.

Little wonder then why there is no wage growth as employers continue hiring mostly those toward the twilight of their careers: the workers who have little leverage to demand wage hikes now and in the future, something employers are well aware of.

Do older workers really have “little leverage to demand wage hikes?” I think it probably depends on the worker and the job. For relatively unskilled, repetitive work, employers will hire whoever is most productive and reliable for the price they want to pay. They’ll pay what it takes to keep those workers aboard and still make a profit. No offense to the younger generation, but the older generation doesn’t stay out and party and shows up ready to work.

I am sure you have had something like the following experience. I walked up to the busy checkout line at the local Barnes & Noble, where a clearly elderly gentleman proceeded to check out the rather complex combination of books, gift cards, and electronic transfers I wanted to buy. He proceeded flawlessly, and I finally had the temerity to ask, “How old are you?” “Eighty-four,” came back the answer; “I like to stay active, and I get to meet a lot of interesting people.” We had a quick conversation about how much more common people like him are today, and I moved on. I got the definite impression that he could live without the income but preferred working. I also recalled my 17-year-old daughter checking me out at Barnes & Noble 20 years ago. So I walked around and sized up the present-day staff and found an age range decidedly skewed from what I remembered 20 years earlier.

Older people may simply be willing to work for less money, although I don’t think Barnes & Noble is paying high salaries to any of its retail clerks. Some have other income sources, such as Social Security. Those over 65 have Medicare, which reduces the employer’s benefit headache. Younger workers have neither advantage.

Nonetheless, I’m still surprised to see younger workers losing so much ground. I hope it’s because they’re busy learning new skills. That’s what we really need.

But there may be something else happening to skew the work force age distribution. There is growing awareness of what is being called the “gig economy.” My hedge fund friend Murat Koprulu has been busy researching and documenting this phenomenon and regularly regales me with what he finds. He goes and spends evening and weekends with young gig workers, trying to figure out what it is they really do and how they make ends meet in New York City. It turns out they need a lot less to support their lifestyle than you might imagine, and they prefer working intermittent gigs, being able to do what they want, and having no boss.

A close look at the data indicates that the gig economy is indeed large and growing. Pushing this growth are Generation Xers, who typically prefer more flexible work arrangements, and Millennials, who often have no other choice. The gig economy is rapidly changing the country’s economic landscape – for better or worse.

It’s not just Uber driving or AirBnB. There are literally scores of websites and apps where you can advertise your services, get temporary or part-time work, and do so from anywhere you happen to be. Some “gigs” actually pay pretty good money, but they are for people with specialized skills who prefer to live a somewhat different lifestyle than the typical 9-to-5’er does.

There is a great deal of debate among economists about how big the gig economy really is. It doesn’t seem to show up clearly in the BLS employment data. Typically, we would expect those working in the gig economy to appear in the self-employed category, but that category is actually drifting downward in numbers, relatively speaking. So the Wall Street Journal recently published an article pooh-poohing the concept of the gig economy.

Not so fast, say Harvard economist Larry Katz and Princeton’s Alan Krueger. They are currently working on research to document the rise of the gig economy America.

From a story at fusion.net:

Katz said two pieces of evidence suggest current measures of self-employment and multiple-job holding are “missing a large part of the gig economy.”

The first is that the share of the employed (and of the adult population) filing a 1099 form, the tax document “gig economy” workers must file, increased in the 2000s, even as standard measures of self-employment declined in the 2000s.

Likewise, the share of individuals filing Schedule C tax forms to report profits and losses for their homegrown businesses is up “substantially” in the 2000s, “even though survey measure of self-employment are down.”

“These discrepancies suggest a growth of ‘gig’ and ‘share’ economy workers who receive 1099 income, file Schedule C forms on their taxes, but don’t answer the standard [government] question as indicating they are self-employed and don’t say they are a multiple job holder,” Katz said.

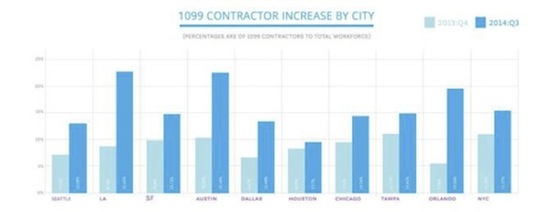

Other groups have confirmed this: Zen Payroll, a site that tracks the sharing economy, found increases in the share of 1099 workers across many major U.S. metros.

Source: Zen Payroll via Small Business Labs

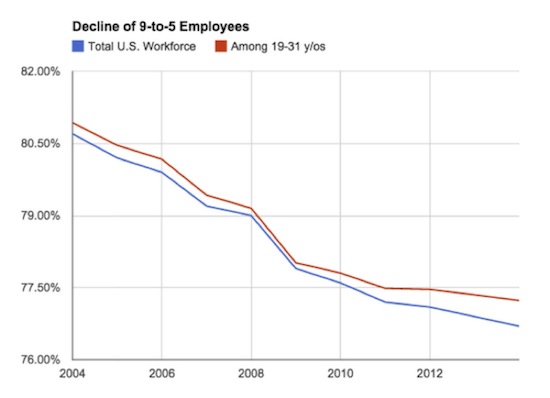

And data from research group EconomicModeling.com show the share of traditional, 9-to-5 workers in the labor force has declined…

Source: Fusion, data via EconomicModeling.com

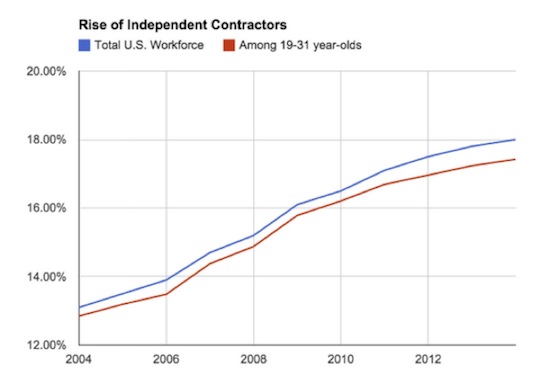

…while those who categorize themselves as “miscellaneous proprietors” is climbing.

Source: Fusion, data via EconomicModeling.com

Meanwhile, in preliminary interviews with “gig economy” workers, Katz said he and Krueger have confirmed that a majority of those who have regular, non-“gig” employment don’t answer that they have “multiple jobs” when asked the standard multiple-jobs question, “even in many cases where they have significant on-line and other non-traditional job income.”

They do answer about their share, gig, and freelance economy activities when specifically asked about other specific ways they made income,” Katz said. “But many of them do not seem to consider such activities as ‘regular jobs.’”

Indeed, a recent survey found 60 percent of such workers get at least 25 percent of their income from gig economy work.

This report absolutely squares with what Murat’s research is showing. He is starting to write a book on the gig economy. I’ve read the outline. I don’t think my age peers will quite understand what’s happening. Their reaction may be akin to how my parents felt about their children in the ’60s and ’70s.

As Steve Hill writes at the Huffington Post:

The gig economy is just one sub domain of what is happening more broadly to the workforce, including just-in-time scheduling and other disruptions to the labor markets, whether as a result of the gig economy, automation and robots, artificial intelligence and other factors. Fortune columnist Jeffrey Pfeffer writes, “What is not in dispute is that the proportion of contractors, freelancers, and part-time, contingent workers in the U.S. has been increasing and has been for a long time.”

What I notice with some of my own children and many of their friends is that the gig economy, and the independent contractor world in general, is almost completely divorced from anything that looks like a social safety network. Healthcare? 401(k)s? Retirement programs? Extra help for single moms? Forget about it.

Murat thinks the phenomenon is reminiscent of black jazz players in the ’20s who traveled from “gig to gig” in different cities around the country, living on the edge but doing what they wanted. That observation triggered the thought for me that it has been roughly 80 years since that time, or about four generations, which is the amount of time Neil Howe says it takes for the generational cycle to begin to repeat. I picked up the phone, called Neil, and asked him about this; and he told me there is a great deal of similarity between the Lost Generation of the Roaring ’20s and Gen Xers today. And as it turns out, he wrote a short essay on the phenomenon of the gig economy, which you can read on his site.

The problem with the BLS estimates is that they leave out a sizable chunk of the true gig economy. Quoting Neil:

Consider this: An agency temp, an on-call staffer, and even a standard part-time employee all find themselves in an irregular work environment – and yet many are ignored by the BLS definition.

What, then, would the gig economy look like if we included all contingent workers? By looking at historical CWS data, the GAO found that a whopping 30.6 percent of laborers were contingent in 2005, up slightly from 1999. Further, by analyzing more recent General Social Survey (GSS) data, the GAO determined that this share grew to 40.4 percent as of 2010. (To be sure, some of this growth may be due to differences in the sample populations surveyed.) If anything, this hefty share underestimates the gig economy. Virtually no full-time workers would self-identify as contingent workers, but at least some alternatively employed individuals – such as a full-time Uber driver – consider themselves regular full-time workers.

The basic picture outlined by the GAO report is gaining acceptance. According to economic journalist Justin Fox, “It is fair to say that somewhere between 30 percent and 40 percent of American workers labor in something other than conventional full-time jobs.” Fast Company agrees: “The sector of workers who don’t have traditional full-time jobs – whether by choice or not – is a sizable and growing portion of the workforce.” A more recent survey commissioned in 2014 by the Freelancers Union finds that 53 million Americans, or 34 percent of the workforce, are essentially freelancers.

Moreover, the gig economy is not only large – but also growing. While it’s true that monthly BLS data show a secular decline in self-employment, other categories of gig work have surged. For example, the same data show that the part-time share of the workforce has risen by about 2 percentage points since the Great Recession. Similarly, we can surmise that independent contractors make up an increasing share of the workforce: According to research by the American Action Forum, the country added over 2 million independent contracting jobs between 2010 and 2014, accounting for nearly 30 percent of all jobs added during that time period. After looking at types of work by industry, economist Gerald Friedman estimates that fully 85 percent of net new jobs added since 2005 have been irregular.

A point that Neil made in our conversation is that unlike my generation (Boomers), who are seemingly defined by our work, the Gen Xer says, “Work is not my life; it’s what’s I do to get a life.”

But outside of the gig economy there is a growing need for skilled workers. My friend Bill Dunkelberg, chief economist of the National Federation of Independent Business, keeps a close eye on small business attitudes and activity. His latest data points to a different problem: employers can’t find enough qualified workers.

The NFIB numbers don’t match what BLS recently reported. According to NFIB, job creation came to a halt in October. Only 12% of businesses they polled reported growing payrolls, while 10% had actually reduced employment. But that isn’t because they don’t want to hire.

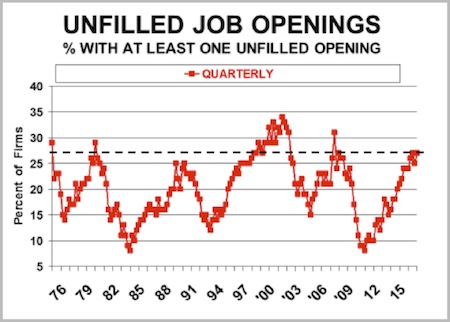

The percentage of small businesses with at least one unfilled job opening is back near pre-recession levels. In addition, some 55% percent say they hired or tried to hire new workers, but 48% report having few or no qualified applicants.

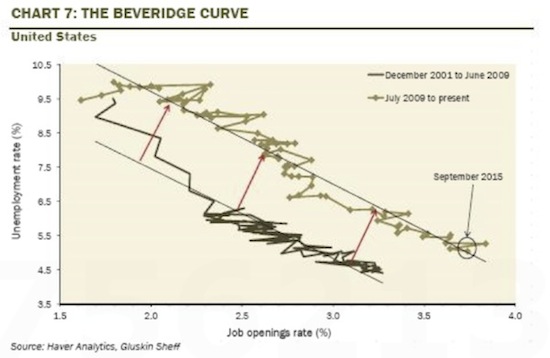

My friend David Rosenberg made the same point last weekend when we were together in Miami, and he wrote about it again today. He thinks that the unemployment rate, rather than underestimating the amount of slack in the labor market, is actually underestimating how tight conditions are. He refers to the Beveridge curve, which is a squiggly looking timeline graph that depicts the relationship between job openings and unemployment. To most people it’s just a confusing doodle, but the point you should take away is this: The employment trendline for 2000–2009 has shifted dramatically during the years since. I find this phenomenon fascinating – just another conundrum to mull over as we think about where the labor market is going. Quoting from Rosie’s piece:

I mean, this inability of firms to fill positions from the current supply of available labor speaks to the structural issues in the labor market rather than anything cyclical.

To further this point, let’s turn to the Beveridge Curve, which plots out the relationship between job openings and unemployment – you can see that there has been a distinct outward shift in the curve in this cycle from where it was before 2009.

What this means is there is a higher unemployment rate for any given level of the job openings rate – for example, based on the prerecession relationship, the 3.7% job openings rate in September (job openings as a share of openings and payroll employment) would be consistent with a 3.0% unemployment rate, not the prevailing 5.0% rate.

This type of change in the relationship is indicative of an inefficient jobs market since the demand for labor by companies is unable to be met by the available supply, and this typically reflects structural issues on the supply side (such as skills or geographic mismatches) rather than a cyclical drop in demand for workers – again, this survey corroborates this. So in this sense, the unemployment rate is actually overstating the degree of slack that exists in the labor market.

This has two main implications. First, since the issues in the labor market are seemingly structural rather than cyclical, there is no amount of monetary policy stimulus that can reasonably be expected to fix this – this is something that needs to be addressed through skills training and related government policy; using monetary policy is a remedy means that rates will be too low for too long and result in credible risk to price stability. (Emphasis mine)

Secondly, this suggests that labor market conditions are in fact increasingly tight and that the nascent uptick that we have seen in wage rates is likely to be sustained as firms looking for qualified labor [are] forced to push wages higher to lure workers.

He has a point – up to a point – but my observation is that firms are only going to have to increase wages for jobs that demand real skills, as opposed to those that merely require warm bodies to show up for work. How, in an economy with almost 8 million unemployed workers, can almost half of our supposedly job-creating small businesses be unable to hire the workers they need?

The answer is that we have a skills gap. The workers who are looking for jobs aren’t qualified for the available job openings. Which suggests that the labor market issue is not about monetary policy. It’s an education and training issue.

If skillful workers exist at some companies, you might expect employers with vacancies to lure those workers away with higher pay packages. Simple supply and demand, right? A higher price should increase the supply. That doesn’t seem to be happening.

Are profit margins so tight that small businesses simply can’t pay enough to hire the skilled workers they need? Maybe so. The inflation data suggests few companies have the ability to raise their prices in this economy (the healthcare sector being a big exception).

Imagine you are one of those small business owners. You sell all the widgets you can make. You can’t increase production without more workers, but you can’t afford more workers unless you raise prices. You can’t raise prices because competing widget makers are eager to grab your customers.

This must be a frustrating situation for those owners. I’ll bet some readers know the feeling.

Cayman Islands

First, let me offer my thoughts and prayers to those of many millions worldwide, in support of the families of those murdered in Paris. The cold-bloodedness and ruthless efficiency with which these killers operated in one of the great cities of civilization is troubling in the extreme. Purposefully shooting at disabled people?

These are not members of any human race that I wish to be thought as part of. We’re going to be dealing with the repercussions from these horrific acts for quite some time.

The schedule in the subhead above sounds hectic, but it’s not really. I fly into Detroit Monday and back out Tuesday, and then I’m not scheduled to fly until early January, when I will spend five days in Hong Kong. More on that in future letters. In late January I will be the keynote speaker at the big ETF conference (ETF.com), where a few thousand people will gather to talk about portfolio design in the world of ETFs.

I’m really looking forward to that. Then I’ll return to the Cayman Islands for a speech in early February. I know I have to get to New York and maybe Washington DC sometime betwixt and between; but for me that is a rather sedate travel schedule, which is good, because I need to be spending most of my time researching and writing.

For the several hundred people who have volunteered to help me research my new book, Investing in an Age of Transformation, you should be hearing from us shortly.

We just had to completely reorganize how we’re going to do the book, and I’m really excited about the process we’re coming up with. It has now become something of a global community project with a book tagged onto the end. I think we’re going to produce something really amazing – a tool to help everybody understand not just how technology is going to change our world but also how geopolitics, sociology, demographics, and the future of work interact with technology. And of course we’ll discuss how to invest in transformative change, so that we can all have the brightest possible personal futures.

I’ve decided to go back and read Andy Kessler’s great little book How We Got Here, which is a hilarious but very insightful take on the progress of technology since the Industrial Revolution. I’ve mentioned the book before –for technology history buffs it’s an essential read to get a complete overview of how we came from the Newcomen steam engine (which didn’t really do much and was dangerous) to the iPad. The book gives you a context for the ongoing technological transformation process. Today it’s almost as if technological progress has taken on a personality and become its own driving, self-evolving force. In an odd sense, it has been the tinkerers and inventors – who have largely been denizens of the gig economy – that have driven human progress.

This week I get to spend Friday with David Brin, Hall of Fame science fiction writer, who actually wrote a book on the importance of tinkering to the progress of science. (Well, it’s a comic book that encouragse young people to “do stuff” rather than just play video games.) And he has arranged for me to have some time with the people at Oculus, to look at what’s coming off the drawing board in the field of virtual reality. Which, come to think of it, I haven’t even thought about putting into my book yet, and how could I miss that one? It will be so big in 10–15–20 years.

My editor, Charley Sweet, just reminded me that he has been hanging out in the gig economy for quite some time. He now lives on a farm somewhere up in Appalachia with his wife Lisa, where they raise goats, chickens, ducks, fruit trees, veggies, etc. – they call themselves “budding permaculturalists” – and are more or less [less! –ed.] prepared for TEOTWAWKI (The End of the World As We Know It, for those of you who aren’t in the know on such matters). In the meantime he and Lisa (MA, English, Duke) edit for me and a bunch of other well-known writers. When I first met him online, some 10–12 years ago, he convinced me to let him edit by actually whaling on my letters week after week and showing me how embarrassed I should be. After the third or fourth go-around we worked out a schedule. He was perched somewhere up in the wilds of Northern California then, way off-grid, and was single at the time, so he could stay up late and make sure the letter got out every Saturday morning.

We are roughly the same age and share a lot of cultural experiences, except that I’m quite a bit more optimistic about the future. But then again, I know where to go if the Malthusians are right. Charley is an interesting character. His highly checkered career has featured stints in community economic development, solar energy systems work, and educational software development [not to mention some years spent as an earnest hippie –ed.]. Oh, and he managed to squeeze in seven years in Japan, where he taught Engrish and knocked out a PhD in Jungian psychology while a research fellow at Kyoto University. He has become quite sedate now that he has moved to a civilized location and Lisa has forced him to live civilized hours, so I can no longer get him to stay up Friday night and into Saturday morning editing and publishing my letter.

And with that it’s time to hit the send button. I hope you have a great week. I’m having about as much fun as one guy can have, working out my own version of the gig economy.

Your wouldn’t want to live any other way analyst,

(Well, I wouldn’t mind flying private, but my part of the gig economy doesn’t pay that well – yet.)

John Mauldin

0 comments:

Publicar un comentario