UBS DEAL SHOWS CLINTON´S COMPLICATED TIES / THE WALL STREET JOURNAL

UBS Deal Shows Clinton’s Complicated Ties

Donations to family foundation increased after secretary of state’s involvement in tax case

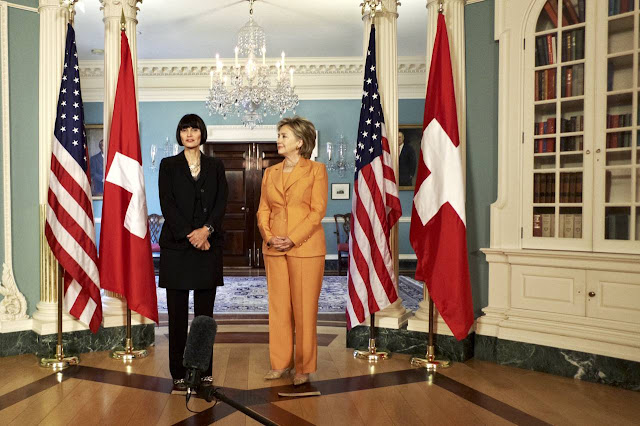

Then-Secretary of State Hillary Clinton appeared with Swiss Foreign Minister Micheline Calmy-Rey, left, at the State Department on July 31, 2009, announcing a deal in principle to settle a legal case involving UBS. Photo: J. Scott Applewhite/AP

A few weeks after Hillary Clinton was sworn in as secretary of state in early 2009, she was summoned to Geneva by her Swiss counterpart to discuss an urgent matter. The Internal Revenue Service was suing UBS AG to get the identities of Americans with secret accounts.

If the case proceeded, Switzerland’s largest bank would face an impossible choice: Violate Swiss secrecy laws by handing over the names, or refuse and face criminal charges in U.S. federal court.

Within months, Mrs. Clinton announced a tentative legal settlement—an unusual intervention by the top U.S. diplomat. UBS ultimately turned over information on 4,450 accounts, a fraction of the 52,000 sought by the IRS, an outcome that drew criticism from some lawmakers who wanted a more extensive crackdown.

From that point on, UBS’s engagement with the Clinton family’s charitable organization increased. Total donations by UBS to the Clinton Foundation grew from less than $60,000 through 2008 to a cumulative total of about $600,000 by the end of 2014, according the foundation and the bank.

The bank also joined the Clinton Foundation to launch entrepreneurship and inner-city loan programs, through which it lent $32 million. And it paid former president Bill Clinton $1.5 million to participate in a series of question-and-answer sessions with UBS Wealth Management Chief Executive Bob McCann, making UBS his biggest single corporate source of speech income disclosed since he left the White House.

There is no evidence of any link between Mrs. Clinton’s involvement in the case and the bank’s donations to the Bill, Hillary and Chelsea Clinton Foundation, or its hiring of Mr. Clinton. But her involvement with UBS is a prime example of how the Clintons’ private and political activities overlap.

UBS is just one of a series of companies that engaged with both the Clinton family’s charitable organization and the State Department under Mrs. Clinton. And it is an unusual one: Unlike cases in which Mrs. Clinton went to bat for American companies seeking business abroad, such as General Electric Co. and Boeing Co. , the UBS matter involved her helping solve a problem for a foreign bank—not a popular constituency among Democrats—and stepping into an area where government prosecutors had been taking the lead.

The flood of donations and speech income that followed exemplifies why the charity and its fundraising have been a running problem for the presidential campaign of Mrs. Clinton, the Democratic front-runner. Republicans as well as some Democrats have raised questions about potential conflicts of interest.

“They’ve engaged in behavior to make people wonder: What was this about?” says Harvard Law Professor Lawrence Lessig, who is a Democrat. “Was there something other than deciding the merits of these cases?”

Critics also have hit the charity for accepting donations from foreign governments, which they say could pose problems for her if she is elected, potentially opening her to criticism that she is obligated to foreign donors.

The Clintons have said accepting donations posed no conflicts of interest and broke no rule or law. To address the criticism, the Clinton Foundation decided to release donation information more frequently, and the foundation said earlier this year that the first disclosure is expected by the end of July.

UBS officials deny any connection between the legal case and the foundation donations. “Any insinuation that any of our philanthropic or business initiatives stems from support received from any current or former government official is ludicrous and without merit,” a bank spokeswoman said. UBS said the speeches by Mr. Clinton and the donations were part of a program to respond to the 2008 economic downturn.

A Clinton campaign spokesman said Mrs. Clinton is proud of the foundation’s work and her record as secretary of state. “Any suggestion that she was driven by anything but what’s in America’s best interest would be false. Period,” he said. He referred questions about the UBS matter to the State Department.

A State Department spokesman said that “UBS was a topic of serious discussion, among other issues, in our bilateral relations at that time” with the Swiss government. A spokeswoman in the Swiss embassy in Washington said the government had no comment.

In a CNN interview last month, Bill Clinton was asked if any foundation donors ever sought anything from the State Department. “I don’t know,” he replied. “I know of no example. But I—you never know what people’s motives are.”

Tax avoidance

UBS’s troubles began in 2007 when an American banker working in Switzerland told the U.S. Justice Department that UBS had recruited thousands of U.S. customers seeking to avoid U.S. taxes. The disclosure led UBS to enter into a deferred-prosecution agreement with the Justice Department in 2009. The bank admitted to helping set up sham companies, creating phony paperwork and deceiving customs officials. It paid a $780 million fine and turned over the names of 250 account holders.

The agreement left unresolved a separate legal standoff over whether UBS—in response to a summons from the IRS—would turn over the names of U.S. citizens who owned 52,000 secret accounts estimated to be worth $18 billion. “We should get all the accounts,” IRS Commissioner Dan Shulman maintained at a Senate hearing in 2009.

After a federal judge indicated he would rule quickly, UBS enlisted the Swiss government to approach the State Department.

“UBS believes this dispute should be resolved through diplomatic discussions between the two governments,” Mark Branson, then chief financial officer of UBS Global Wealth Management and Businesses, said at a separate congressional hearing.

John DiCicco, then the Justice Department’s top tax lawyer on the case, responded at the same hearing: “We are not going head-to-head with the Swiss government, but UBS.”

Mrs. Clinton’s role in resolving the matter was more extensive than previously reported. She didn’t initiate her involvement in the case, but was drawn into it by separate diplomatic concerns, according to interviews with people involved in the case and diplomatic cables first published by WikiLeaks.

On March 6, 2009, two days after the congressional hearing, Mrs. Clinton met Swiss Foreign Minister Micheline Calmy-Rey for the first time. Ms. Calmy-Rey suggested settling the UBS matter through the U.S.-Swiss treaty process.

But Mrs. Clinton also wanted to talk about other matters of concern to the U.S. She brought up a U.S. journalist jailed in Iran, the State Department said. The U.S. hadn’t had direct diplomatic relations with Iran since 1979, and the Swiss embassy in Tehran represented U.S. interests in Iran.

She also wanted to discuss a Swiss-based energy-consulting company, Colenco AG, that allegedly was violating international sanctions by providing civilian-nuclear technology to Iran, according to a State Department cable that July 1. And Mrs. Clinton wanted Switzerland to take some low-risk detainees from the prison in Guantanamo Bay, which President Barack Obama has vowed to close, according to the cable.

After the meeting broke up, Ms. Calmy-Rey spoke to reporters about the importance of resolving the UBS problem: “It was not in our common interest for the situation to escalate further as UBS is responsible for 30,000 jobs in the U.S., and the bank’s difficulties could weaken the international financial system.”

A State Department official wrote after the meeting in another cable that the UBS case was “a dark cloud over bilateral relations, with concerns it could escalate to a seriously damaging event.” The State Department declined to comment on any of the cables made public by WikiLeaks.

The Swiss appeared to act on Mrs. Clinton’s concerns. That May, the U.S. journalist was released. On July 1, the Swiss trade minister told the U.S. that Colenco would shut down its Iran operations. (The company said none of its activities violated international sanctions.) Economy Minister Doris Leuthard also expressed Switzerland’s willingness to accept Guantanamo detainees.

Ms. Leuthard, referring to Guantanamo and Iran, “made it clear that these two activities were linked to the achievement of a political settlement in the case of Swiss banking giant, UBS,” the July 1 cable said.

After the cable became public, Ms. Leuthard told a Swiss newspaper there was “no direct connection” between UBS and the Iran and Guantanamo issues. A Swiss embassy spokeswoman said Ms. Leuthard had no comment.

Out-of-court negotiations to settle the case intensified, according to lawyers involved in the case.

In mid-July, Ms. Calmy-Rey told a Swiss reporter she expected a resolution by the time she met with Mrs. Clinton in late July in Washington. She said the U.S.-Swiss relationship was at stake.

On July 31, Ms. Calmy-Rey appeared with Mrs. Clinton at the State Department to announce a deal in principle. The Justice Department and IRS agreed to dismiss the lawsuit and settle the disagreement under a U.S.-Swiss tax treaty, as Ms. Calmy-Rey had sought. UBS would turn over information on about 4,450 accounts, not 52,000.

“Our governments have worked very hard to reach this point,” Mrs. Clinton said.

Ms. Calmy-Rey called the agreement a “Peace Treaty” and UBS praised it.

Then-Sen. Carl Levin (D., Mich.), a longtime advocate of cracking down on tax avoiders with offshore accounts, criticized the deal. “It is disappointing that the U.S. government went along,” he said.

Carolyn Schenck, a senior counsel at the IRS, said at a conference earlier this year that many U.S. citizens with overseas accounts escaped IRS scrutiny in the settlement.

An IRS spokesman defended the deal, saying it had “resulted in criminal prosecutions, produced billions in penalties and taxes and forced a dramatic shift in the use of offshore banks to hide money.”

A Justice Department spokeswoman said the department has criminally charged 66 people who had UBS accounts, though she couldn’t say whether any of those cases were related to the settlement.

State warning

Mr. DiCicco, the senior Justice Department tax lawyer on the case who has since retired, said the State Department didn’t get involved in details of the settlement, but did warn about the ramifications of taking a tough line.

“There is a risk that if a large bank is indicted it would lose its ability to do business in the U.S.,” he said. “That was a consideration.” He said there was no “pressure” from the State Department on that issue.

As loose ends of the deal were being tied up in late 2009, UBS began making plans to create a small-businesses program. In early 2010 it decided to team up with a Clinton Foundation project called the Clinton Economic Opportunity Initiative.

UBS started a pilot entrepreneurs program in New York City in June 2011 with a $350,000 donation to the foundation, according to the bank. Its only previous donations were “membership fees” of about $20,000 a year. The 2011 donation also paid for an earlier appearance by Mr. Clinton at a UBS event where he discussed the economy, the bank said.

In 2012 the entrepreneurs program was listed as one of three of the Clinton Economic Opportunity Initiative’s most significant achievements of the year. UBS ultimately offered $32 million in loans to dozens of businesses in six cities. (The money didn’t go to the foundation.)

The bank dubbed the program Elevating Entrepreneurs and packaged it with appearances around the country by Mr. Clinton and former President George W. Bush.

Mr. Clinton earned $1.5 million for 11 appearances in New York, Dallas, Miami, Pittsburgh, San Francisco, Nashville and other cities. Mr. McCann, the UBS Wealth Management executive, conducted the panel discussions with Messrs. Clinton and Bush. Spokesmen for Mr. Bush and UBS declined to comment on how much Mr. Bush was paid.

UBS also gave $100,000 to the Clinton Foundation for a charity golf tournament.

Stu Gibson, who litigated the lawsuit against UBS for the Justice Department, said in a recent interview that he was unaware that the bank had increased its donations to the Clinton Foundation in the wake of the settlement.

“It raises questions that need to be addressed, or should be addressed,” said Mr. Gibson, who has left the government and now is editor of Tax Notes International. “Maybe there’s nothing to it. Maybe there is something to it.”

0 comments:

Publicar un comentario