Fight the power

Investors are being pressed to sell their holdings in coal, oil and gas

Jun 27th 2015

.

ON JUNE 1st a pressure group called “Reclaim the Power” organised a day of action against the energy industry in Britain, including blockades of offices, protests at art galleries sponsored by oil firms and a 1960s-style “love-in” in which agitators lay in a bed outside one of David Cameron’s offices in an effort to persuade the prime minister to become greener.

Their actions were part of a wider campaign, marshalled by 350.org, that seeks to dissuade investors from owning shares in the companies that produce fossil fuels and thus contribute to climate change. So far the protesters have managed to persuade 220 cities and institutions to divest some of their holdings, varying from the very small (the Australian Guild of Screen Composers) to the large (the $21 billion endowment of Stanford University). This month the campaign landed its biggest recruit yet: Norway’s sovereign-wealth fund, which has assets of almost $900 billion, agreed to sell $9 billion-worth of shares in firms that mine coal and tar sands, a particularly polluting form of oil.

Divestment is not a new idea. A campaign against the apartheid regime in South Africa got going in the 1980s; others have long been waged against the arms trade and tobacco firms. Recently, activists have targeted Israel for its treatment of Palestinians; their campaign is known as BDS (boycott, divestment and sanctions).

Such protests naturally result in passionate debates about the rights and wrongs of each issue.

But they also raise practical issues for investors considering whether to take part. The most obvious for money managers is whether divestment is a negation of the “fiduciary duty” to safeguard the interests of their beneficiaries, be they future pensioners or the citizens of Norway, by earning the highest possible return. Tobacco companies, critics of divestment point out, have yielded fantastic returns, despite much public opprobrium, gargantuan legal settlements and ever more stringent restrictions on smoking.

On the other hand, there is little evidence that ethical investing—or its close cousins, sustainable investment, environmental, social and governance (ESG) policies and corporate social responsibility (CSR)—diminish returns. A survey published in 2009 of academic papers that focused on CSR, including environmental measures, found a mildly positive correlation between the pursuit of socially responsible policies and financial performance. A more recent study by MSCI, an index firm, covered the period from February 2007 to March 2015; it found that investment portfolios with greater exposure to firms with high ESG ratings, or to firms that had recently increased their rating, performed better than the market as a whole.

On the specific issue of climate change, Mercer, an actuarial consultancy, recently issued a report that argues, “Investors cannot assume that economic growth will continue to be heavily reliant on an energy sector powered predominantly by fossil fuels.” If climate change begins to cause economic and social havoc, governments will have to act, either by restricting energy use or by taxing carbon emissions. In such circumstances, Mercer contends, it will not be possible for energy companies to exploit all their known reserves: some will become “stranded assets”. The average annual returns from coal could fall by anywhere between 18% and 74% over the next 35 years, the report concludes. If such estimates are right, then eliminating exposure to the sector would be perfectly compatible with fiduciary duty.

A second question is whether divestment will make any difference to firms’ behaviour. It is impossible to sell an energy company’s shares without a buyer, and the buyer will presumably care less about climate change. For the energy company, life may even get easier.

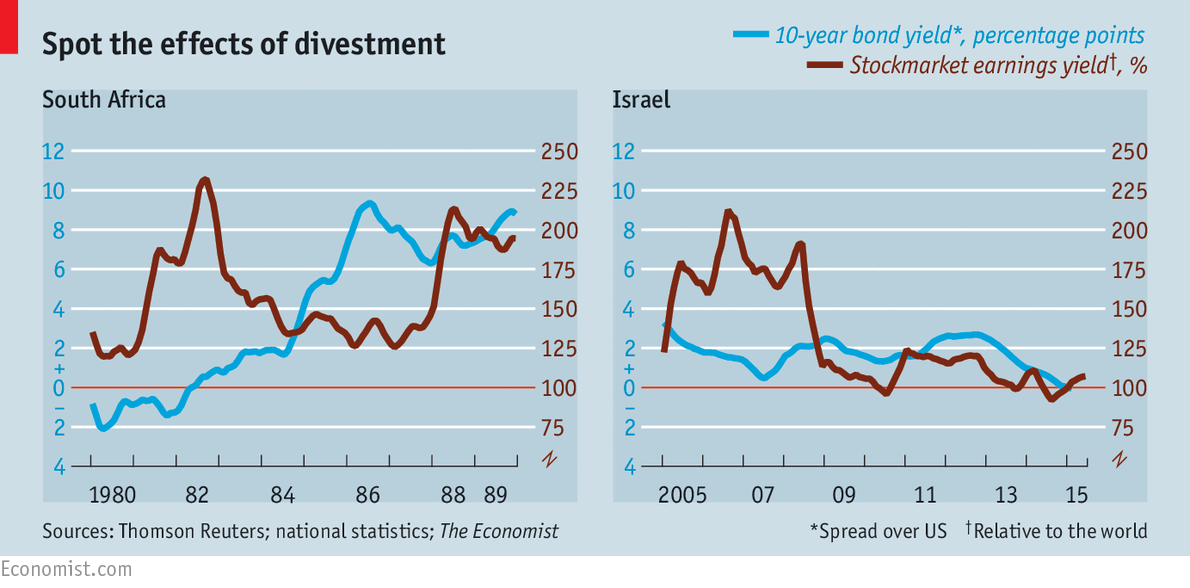

Clearly, if a critical mass of investors refused to own the shares or bonds of a company (or of firms from a particular country), the reduced demand would show up in a higher cost of capital. However, it is very hard to isolate the impact of divestment campaigns from other factors. The first chart on the previous page shows South Africa’s bond yield (relative to Treasury bonds) and the price-earnings ratio of its stockmarket, relative to the global index, in the 1980s, as the campaign against apartheid was gaining strength. The cost of capital for the government and local firms did indeed rise. But the South African economy was heavily dependent on gold mining at the time, and the fall in the bullion price may have been a bigger factor. The second chart shows the price-earnings ratio and relative bond yield of Israel since BDS started in 2005; if anything, the country’s cost of capital has fallen. Its booming tech and pharmaceutical industries and a big gas discovery have caused capital to flood into the country, boosting growth and improving the fiscal Outlook.

.

However, Danielle Paffard, who co-ordinates 350.org’s divestment campaign in Britain, says raising the cost of capital isn’t really the point. The real aim is to deny energy companies the political, social and cultural backing to influence decisions on climate change. The parallel is with the tobacco industry, where the lobbying power of cigarette-makers was eroded over time, paving the way for curbs on smoking in the name of public health. The motivation is also moral: “Climate change will have a particularly severe impact on the poorest and most vulnerable who have contributed least to the problem,” Ms Paffard says.

Public enemy

For investors concerned by climate change, another option is engagement. Saker Nusseibeh of Hermes Investment Management says, “The divestment campaign makes more people aware of the problem but it doesn’t solve the issue. It merely passes it on to the next owner.” Instead, Hermes might try to persuade a coal-mining firm in its portfolio not to develop new mines and instead pass the profits from its existing operations to shareholders as dividends. By the same token PFZW, a giant Dutch pension fund, is asking fossil-fuel producers to invest in cleaner technologies. At the same time, it is increasing its investments in renewable energy and clean technology, aiming to quadruple them by 2020.

Divestment campaigners know they are in for the long haul. Energy producers have seen their share prices slide over the past year—but that is down to a lower oil price, rather than an environmental epiphany among investors. Ironically, the price slide has been driven by the emergence of fracking as a new source of oil: something green campaigners are dead against.

But tougher regulations to stem climate change are also emerging. The battle for hearts and wallets, like the planet, is heating up.

0 comments:

Publicar un comentario