Only a tailwind

A weaker currency will help but cannot rescue the stagnant euro zone

Jan 31st 2015

BERLIN, MADRID, MILAN AND PARIS

ONLOOKERS could be excused for thinking that Christmas had come again to the euro zone this month. On January 22nd the European Central Bank (ECB) said it was ready to buy over €1 trillion ($1.1 trillion) of sovereign and asset-backed bonds between March 2015 and September 2016. Growth, jobs and an end to the spectre of deflation were euphorically invoked by politicians, businessmen and journalists.

The immediate result was to grease the skids under the sliding euro, worth $1.13 at mid-week.

It is now down by 19% against the dollar since May 2014, and by 10% against its trading partners’ currencies. Most think it has further to fall.

This is good news for the euro zone, especially weaker members like France and Italy where many firms struggled to sell their products when the euro was higher. “My dream is parity” of the euro with the dollar, said Matteo Renzi, Italy’s prime minister, at a meeting of the economic great and good at Davos. A cheaper euro should boost economic activity by making exports more competitive abroad and domestically produced goods more attractive at home. There are signs that this is beginning to happen.

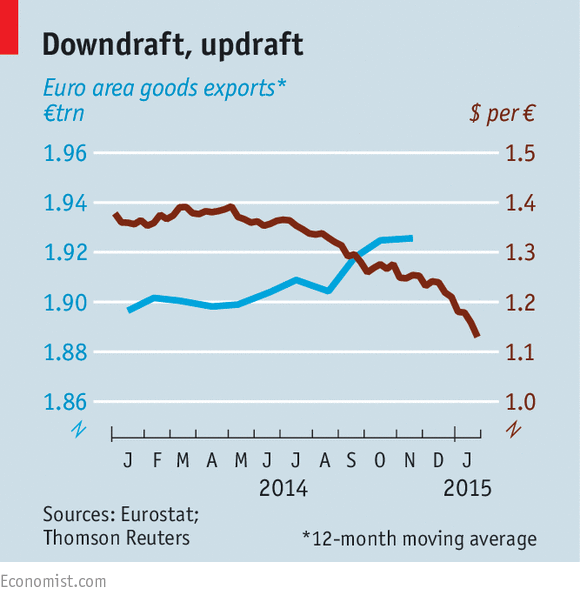

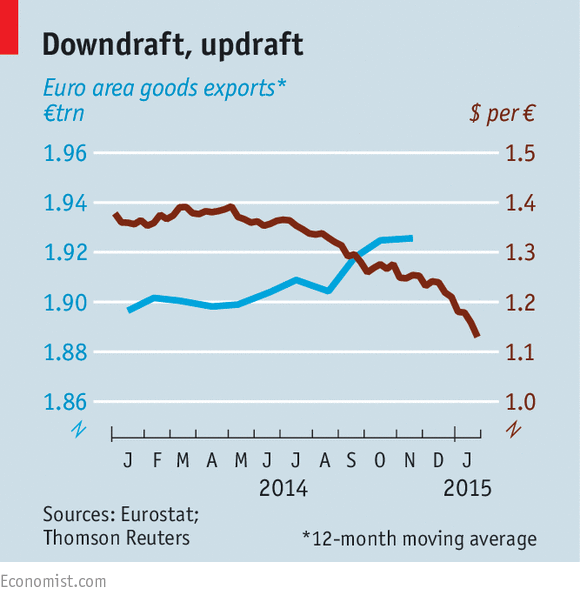

Euro-zone goods exports were 2% higher by value in the 11 months to November 2014 than in the same period a year earlier, on preliminary figures, with growth picking up in the second half of the year (see chart). In the first ten months they increased by 7%-8% to the euro area’s main trading partners—Britain, America and China—where currencies have strengthened. Imports from those countries increased by less or fell.

.

The weaker euro is only one factor: the pick-up in demand in America and Britain, along with the fall in oil and commodity prices, are others. But exchange rates matter. Italy’s export-credit agency estimates that a 10% depreciation in the euro-dollar exchange rate could boost the real value of the country’s exports by up to 1.5% in 2015. Companies should reap the benefit, in the form of either greater sales volumes or fatter margins. The FTSEurofirst 300 share index hit a seven-year high the morning after the ECB’s announcement.

Among the industries likely to benefit are carmakers, chemicals and consumer goods, and especially companies with costs in euros and sales in strong-currency, growing markets like America and Britain.

Carlos Ghosn, chief executive of Renault, a French car company, says that the weaker euro will allow industries with excess capacity in Europe to raise production without costly investment in new plant. Every 1% drop in the euro against the dollar should add 0.5% to earnings per share, Sanofi, a French drugs firm, said in October.

The German Engineering Association believes the euro’s dramatic drop against the Swiss franc (the Swiss Central Bank abandoned the franc’s three-year link to the euro on January 15th) will push more buyers of precision machines and machine tools their way. Indra, a Spanish technology company with two-thirds of sales abroad, says the weak euro gives it an edge when competing against American rivals for dollar-denominated contracts. Accor, Europe’s largest hotel group by beds, reported a healthy increase in occupancy rates in the second half of 2014. Ski resorts in France and Austria are hoping to draw custom from pricey Switzerland.

Makers of luxury goods are cheerful too, even though they normally insist that brand and quality, rather than price, fuel their sales. Château Latour exports 85% of its fine wines outside the euro zone. Jean Garandeau, the company’s commercial director, says that though both its costs and direct sales are in euros, a cheaper currency may encourage distributors to stock up.

But cheaper euros mean costlier imports. Riccardo Illy, chairman of the eponymous group that owns coffee, tea, chocolate and wine businesses, says that although they have increased margins over the past three months by keeping dollar prices stable as the euro has fallen, the overall effect has been negative: the group must buy dollars to import coffee, tea and cocoa. For many companies, though, this effect is mitigated by the lower cost of energy (oil is priced in dollars) and of energyintensive goods.

Though individual companies may gain greatly, the overall impact of the cheaper euro on the continent’s economy is likely to be less dramatic. It is not just that almost half of euro-zone countries’ exports of goods go to other members of the block; those products may still take market share from harder-currency rivals. But most of Europe’s big companies are increasingly far-flung.

More than two-thirds of the workforce of the French firms that make up the CAC 40 share index were based abroad in 2012, according to calculations by Les Echos, a business daily.

Many firms produce in the countries they sell to, or find other ways to match a portion of ongoing costs and revenues. Such “natural hedges” limit the impact of exchange-rate changes. At Safran, a French aerospace and defence firm, half of non-euro revenues (which make up 80% of total revenues) are hedged with non-euro costs. Safran aims to protect the rest of its exposure three years out using derivatives.

In faster-moving, lower-margin industries such as clothing, firms are less inclined to pay for that kind of protection: Inditex of Spain is believed to be one that does not. But only a portion of most big companies’ operations are directly sensitive to currency movements. Peter Oppenheimer of Goldman Sachs, an investment bank, says that nowadays the main impact of foreign-exchange movements is “translational”—determining the rate at which revenues and profits abroad are converted into a firm’s reporting currency for accounting purposes—and not operational.

In any event, it takes time for currency movements to feed through to the real economy in the form of bigger market shares, fatter margins, new jobs or new investment. French firms are among the least profitable in Europe; most may want to rebuild margins before they set about producing more to sell abroad. Many German exports are of high-value-added products for which demand reacts little to price changes: cheapening by 10-20% will not reverse the slowdown in exports to the pinched Chinese consumer. Spain’s sales abroad were already buoyant because firms had cut costs and prices.

The very speed of this currency realignment may make business executives hesitate to base big investment decisions on it, says Ross McInnes, Safran’s deputy chief executive.

He also points out the danger of mistaking the trees for the wood. What matters more than currency fluctuations in trade is demand, and world growth is soggy. A weaker euro will help Europe’s firms, but it is only part of a bigger picture.

The immediate result was to grease the skids under the sliding euro, worth $1.13 at mid-week.

It is now down by 19% against the dollar since May 2014, and by 10% against its trading partners’ currencies. Most think it has further to fall.

This is good news for the euro zone, especially weaker members like France and Italy where many firms struggled to sell their products when the euro was higher. “My dream is parity” of the euro with the dollar, said Matteo Renzi, Italy’s prime minister, at a meeting of the economic great and good at Davos. A cheaper euro should boost economic activity by making exports more competitive abroad and domestically produced goods more attractive at home. There are signs that this is beginning to happen.

Euro-zone goods exports were 2% higher by value in the 11 months to November 2014 than in the same period a year earlier, on preliminary figures, with growth picking up in the second half of the year (see chart). In the first ten months they increased by 7%-8% to the euro area’s main trading partners—Britain, America and China—where currencies have strengthened. Imports from those countries increased by less or fell.

.

The weaker euro is only one factor: the pick-up in demand in America and Britain, along with the fall in oil and commodity prices, are others. But exchange rates matter. Italy’s export-credit agency estimates that a 10% depreciation in the euro-dollar exchange rate could boost the real value of the country’s exports by up to 1.5% in 2015. Companies should reap the benefit, in the form of either greater sales volumes or fatter margins. The FTSEurofirst 300 share index hit a seven-year high the morning after the ECB’s announcement.

Among the industries likely to benefit are carmakers, chemicals and consumer goods, and especially companies with costs in euros and sales in strong-currency, growing markets like America and Britain.

Carlos Ghosn, chief executive of Renault, a French car company, says that the weaker euro will allow industries with excess capacity in Europe to raise production without costly investment in new plant. Every 1% drop in the euro against the dollar should add 0.5% to earnings per share, Sanofi, a French drugs firm, said in October.

The German Engineering Association believes the euro’s dramatic drop against the Swiss franc (the Swiss Central Bank abandoned the franc’s three-year link to the euro on January 15th) will push more buyers of precision machines and machine tools their way. Indra, a Spanish technology company with two-thirds of sales abroad, says the weak euro gives it an edge when competing against American rivals for dollar-denominated contracts. Accor, Europe’s largest hotel group by beds, reported a healthy increase in occupancy rates in the second half of 2014. Ski resorts in France and Austria are hoping to draw custom from pricey Switzerland.

Makers of luxury goods are cheerful too, even though they normally insist that brand and quality, rather than price, fuel their sales. Château Latour exports 85% of its fine wines outside the euro zone. Jean Garandeau, the company’s commercial director, says that though both its costs and direct sales are in euros, a cheaper currency may encourage distributors to stock up.

But cheaper euros mean costlier imports. Riccardo Illy, chairman of the eponymous group that owns coffee, tea, chocolate and wine businesses, says that although they have increased margins over the past three months by keeping dollar prices stable as the euro has fallen, the overall effect has been negative: the group must buy dollars to import coffee, tea and cocoa. For many companies, though, this effect is mitigated by the lower cost of energy (oil is priced in dollars) and of energyintensive goods.

Partial pass-through

More than two-thirds of the workforce of the French firms that make up the CAC 40 share index were based abroad in 2012, according to calculations by Les Echos, a business daily.

Many firms produce in the countries they sell to, or find other ways to match a portion of ongoing costs and revenues. Such “natural hedges” limit the impact of exchange-rate changes. At Safran, a French aerospace and defence firm, half of non-euro revenues (which make up 80% of total revenues) are hedged with non-euro costs. Safran aims to protect the rest of its exposure three years out using derivatives.

In faster-moving, lower-margin industries such as clothing, firms are less inclined to pay for that kind of protection: Inditex of Spain is believed to be one that does not. But only a portion of most big companies’ operations are directly sensitive to currency movements. Peter Oppenheimer of Goldman Sachs, an investment bank, says that nowadays the main impact of foreign-exchange movements is “translational”—determining the rate at which revenues and profits abroad are converted into a firm’s reporting currency for accounting purposes—and not operational.

In any event, it takes time for currency movements to feed through to the real economy in the form of bigger market shares, fatter margins, new jobs or new investment. French firms are among the least profitable in Europe; most may want to rebuild margins before they set about producing more to sell abroad. Many German exports are of high-value-added products for which demand reacts little to price changes: cheapening by 10-20% will not reverse the slowdown in exports to the pinched Chinese consumer. Spain’s sales abroad were already buoyant because firms had cut costs and prices.

The very speed of this currency realignment may make business executives hesitate to base big investment decisions on it, says Ross McInnes, Safran’s deputy chief executive.

He also points out the danger of mistaking the trees for the wood. What matters more than currency fluctuations in trade is demand, and world growth is soggy. A weaker euro will help Europe’s firms, but it is only part of a bigger picture.

0 comments:

Publicar un comentario