Nick Butler

Jan 04 12:00

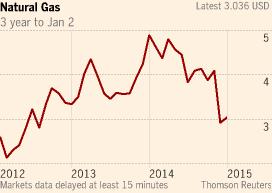

The process of adjustment in the energy market is far from over. After the dramatic halving of the oil price since June there is now every chance that natural gas will follow suit.

Indeed the fall has already begun. During December, US natural gas prices fell below $3 per million British thermal units for the first time since 2012. But that is just the beginning.

Two further factors suggest a continued, and worldwide decline in 2015. First, in Europe in particular, gas supply contracts — for instance from Gazprom into Germany — are tied to the oil price. The link is historic and is gradually giving way to direct gas-to-gas competition. But the older, longer term contracts remain in place for now and that means that a radical downward shift in prices will occur through the coming year.

Secondly, after years of uncertainty since the 2011 Fukushima disaster, there are signs that Japan is ready to accept the gradual reintroduction of nuclear power. The initial steps will be small — perhaps just one or two reactors at first. But even that will be sufficient to undermine gas prices in Asia which rose at times to almost $20/mmbtu as Japan was forced to substitute imported gas for nuclear. Each nuclear station brought back online will reduce demand for gas, and just as prices surged in 2011 now they will slip back. A Reuters survey of some serious analysts, including Wood Mackenzie, forecast a fall of up to 30 per cent in Asian natural gas prices in 2015.

Unlike the oil market, none of this has anything to do with the collapse of a producers’ cartel (or depending on your world view, with a dastardly plan to use falling prices to undermine one political enemy or another). Nor does it have anything to do with Ukraine or the relations between Russia and Europe. There is no gas cartel and no producer has the power to set prices.

The falling price is simply a matter of supply and demand. Supply is strong — driven on by high prices in the last few years and by the US shale revolution. Demand on the other hand is fragile and in Europe is being continuously eroded by subsidised renewables.

The trend in prices is bad for producers, of course, and particularly for Gazprom, which has seen its European sales fall by 9 per cent in the last year. In the US the shale industry appears determined to absorb the pain, for now at least, but there — and elsewhere — there must be a big question mark over new gas investments. Substantial amounts of gas in east Africa, the eastern Mediterranean, Alaska and Australia look likely to stay in the ground for the time being. In some cases costs can be reduced and margins cut, but the most vulnerable companies are those already investing in half-finished projects, which need prices to be maintained to produce the required returns.

Shale gas projects around the world are also in jeopardy. China will presumably continue with its development plans for reasons of energy security and employment, but in the UK the dearth of drilling activity in 2014 looks set to continue. The UK shale gas revolution is postponed.

Lower natural gas prices clearly have a knock-on effect in the electricity market, putting further downward pressure on coal prices and making new nuclear look even more expensive. The fall will also make the notion of freezing electricity bills redundant. To freeze prices which are falling is hardly good politics.

How far will this downward wave go?

At the basic level the answer is that the global market will have to find a new equilibrium and that will only come after a period of volatility. Supply and demand will have to be realigned and that is not a simple process in an industry where for most producers, operating costs (as opposed to the initial capital costs) are very low. Some production, including some US shale gas, can be held back temporarily, but as long as operating costs are being covered there is absolutely no incentive for producers to shut in capacity.

Eventually the cycle will turn. New investment will go down to the point where capacity is fully utilised, and then the cycle begins again. In many cases gas is a good example of economics in action and a business less shaped by politics than most parts of the energy sector. For natural gas, the duration of the present downward trend depends more than anything on the pace of demand growth in the emerging economies of China and India.

In China the issue is made more complex by the uncertain prospects for shale gas. The country has extensive shale resources but development has been slower than many hoped. However if Chinese shale becomes available soon and in substantial quantities, as suggested by some optimistic recent statements from Sinopec (who operate the important pioneer venture at Fuling), China will import less gas than most forecasters now expect, with an inevitably negative impact on world prices. In India, the future is clouded by doubts about the ability of even Narendra Modi’s government, which came to power with an exceptionally strong electoral mandate, to reform the energy market and put in place the infrastructure required if gas is to displace even part of the planned increase in coal consumption. In both cases the evolution of the market will take time. For the moment, across the world there is more available gas supply than demand, and in a buyers’ market, prices can only fall.

0 comments:

Publicar un comentario