Nov. 15, 2014 7:26 AM ET

Summary

- The flash GDP estimate for Q3 released on Nov. 14, together with final inflation data for October, confirm a bleak picture for the euro area.

- Anemic growth of 0.2% over the quarter, and price rises of just 0.4% over the past 12 months hardly make for a happy state of affairs.

- Above all, they do nothing to help the public finances – particularly in Italy, the proverbial ‘elephant in the room’. The ECB knows all of this.

- Extending the maturity terms of TLTROs and buying non-financial corporate bonds are both on the table.

- We expect to hear more in this regard after the next policy meeting, by which time policymakers will have a new set of staff forecasts.

In the end, the ECB will opt for QE, something we expect to be announced in the first half of next year. In our view, the focus will be on Bunds - in accordance with the 'capital key'. QE will buy policymakers time, but it will not solve the crisis

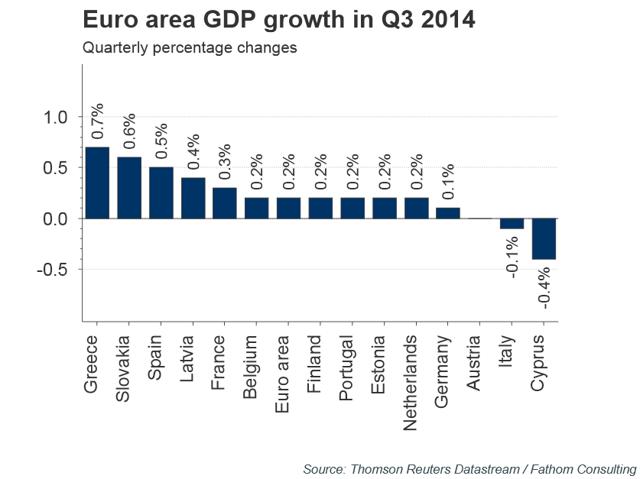

According to Eurostat's flash estimate, released earlier today, the euro area economy grew by a mere 0.2% in Q3, after registering growth of 0.1% in Q2. Germany, once the common currency area's locomotive, appears to have run out of steam, with GDP essentially unchanged over the past six months. With a 0.1% fall in GDP for Q3, Italy chalked up a second consecutive negative quarter and entered a technical recession. There was some positive news from other peripheral economies. With quarterly, seasonally adjusted data published for the first time this morning, it now appears that Greece officially emerged from recession - one of the longest on record for any country - in Q1 2014.

The economy expanded by a further 0.7% in Q3. Spain also enjoyed a relatively high rate of growth - at 0.5%. At the same time, Eurostat confirmed the October annual inflation rate at 0.4% - still far from the ECB's stated target of "below, but close to, 2% over the medium term".

The currency union lacks a number of ingredients necessary for a meaningful acceleration in economic activity - a healthy banking system being the most important. As a result, downward pressure on prices will persist.

The elephant trumpets

In our latest quarterly forecast, we identified Italy as the elephant in the room. And the elephant is, at long last, beginning to trumpet. Nine out of fifteen Italian banks failed to reach the levels of capital required by the ECB's stress tests. Italian banks reported a capital shortfall of €9.7 billion that reduces to €3.3 billion euros when considering capital actions taken in 2014 - both figures being the highest among all countries. What is more, despite the fact that a few countries in the single currency bloc are already labouring under negative rates of inflation, regulators opted not to consider the consequences of a prolonged period of deflation - had they done so we expect that Italian banks would have fared worse still.

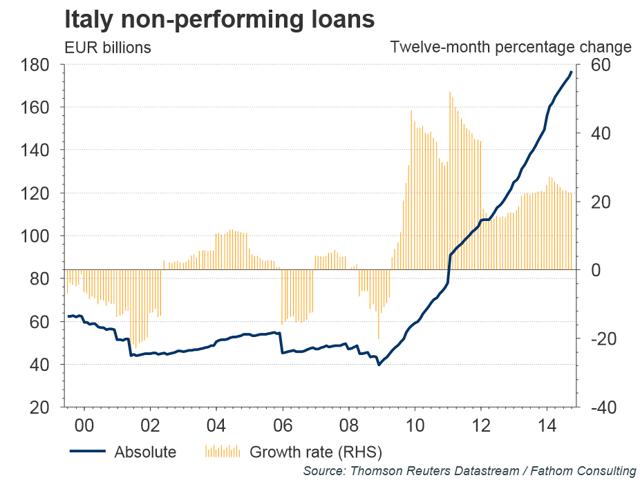

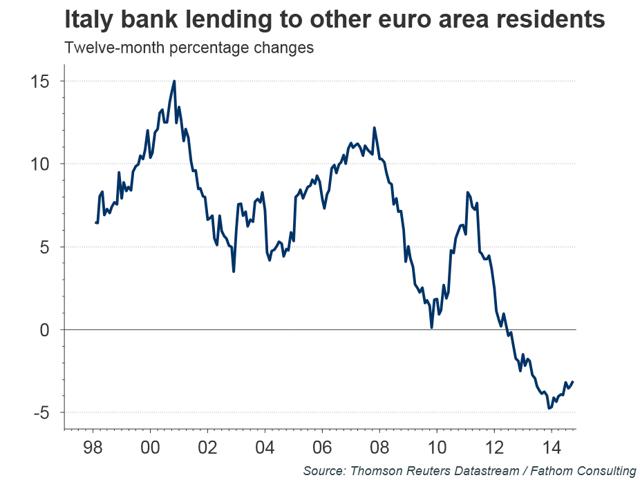

Although the cut-off date for the ECB's stress test and Asset Quality Review was December 2013, non-performing loans (NPLs) at Italian banks have been waxing since then, while lending to the private sector has been waning - month after month. Since December 2013, NPL levels have jumped by €21.0 billion and stood at €176.9 billion in September 2014.

The difficulty, of course, is that Italy is far too big to be given a bailout along the lines extended to Greece, Portugal and Ireland. Its sovereign debt stands at €2 trillion when the combined debt of the other three bailed out countries amounted to €710 billion. In Italy, the problem is the sovereign itself, rather than the banks. With an average maturity of around six years, the country has to refinance over €300 billion of BTPs every year - the same as the entire outstanding stock of Greek government debt.

The ECB, together with politicians across the single currency bloc, are fully aware of the brewing Italian debt crisis, and hopefully, the implications of not dealing with it. We expect them to act, and soon. The only question now is 'How?'.

Unanimity papers over dissent

Following the latest ECB policy meeting, Mario Draghi announced that the decision to raise the central bank's balance sheet by at least €1 trillion thereby returning it to 2012 levels, using further unconventional policy measures if these proved necessary, was unanimous. However, this does not mean that QE, by which we mean sovereign bond purchases, is just around the corner. According to a Reuters exclusive earlier this week, sources close to the ECB have admitted that "[the] current plan to buy private sector assets may fall short and pressure is likely to build for bolder action early next year, firstly moving into the corporate bond market." The news agency goes on to cite the same sources as claiming that perhaps one-third of the ECB's Governing Council members remain opposed to the idea of QE.

How might we square the evident dissent in the ranks, with the apparent determination of all concerned that the ECB's balance sheet must be returned at least to 2012 levels? In our view, the dissenting group of nations - led by Germany - sees the need for further action to halt the slide towards deflation, and thereby safeguard the very existence of the common currency. But they still believe that this can be achieved without the need for QE. So, they would rather explore all other options and attempt to make them work. These include improved TLTRO terms (such as extending the maturity over four years) and the inclusion of non-financial corporate (NFC) debt in the asset purchase remit.

Indicated moves unlikely to work

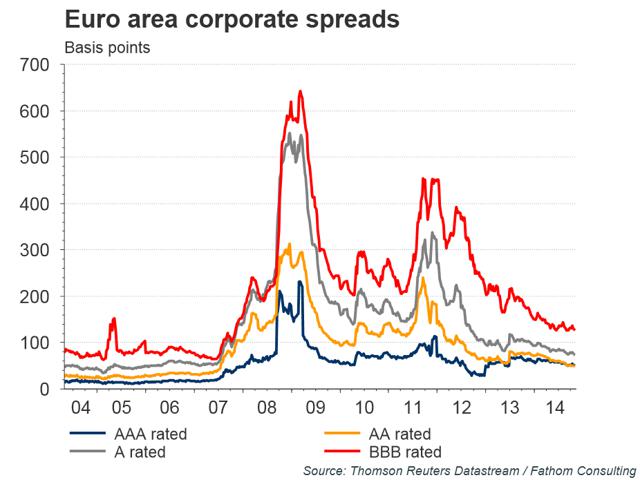

We believe that improved TLTRO terms, while desirable, would do little to alter the economic landscape of Europe. According to Frankfurt, NFC bond purchases would ease credit conditions for corporates, and stimulate demand for credit. We see two issues here. First, SMEs - largely unable to fund themselves in the bond market - would be left out. Second, large corporates - the main bond issuers - have no need of such largesse. Spreads are back almost to pre-crisis levels and corporate issuance has been buoyant since 2012. In fact, the current yearly growth rate of the outstanding amount of NFC bonds already stands at 9%.

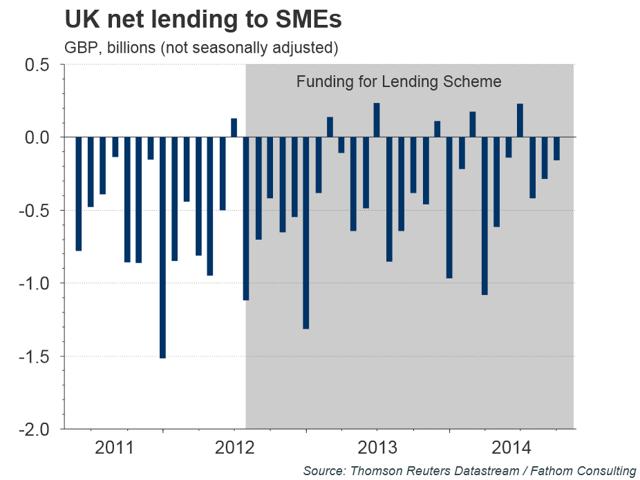

Some might argue that supporting corporate issuance would force banks to channel funds towards SMEs. But if the BoE's Funding for Lending Scheme (FLS) scheme has taught us anything, it is that we cannot take this for granted. Despite reducing bank funding costs, the FLS has done little to arrest the decline in the amount of bank credit afforded to UK SMEs, as our chart shows. The fragile nature of the balance sheets of UK banks means that they were, and still are reluctant to lend to inherently risky, less well-established firms. The balance sheets of euro area banks are certainly in no better shape.

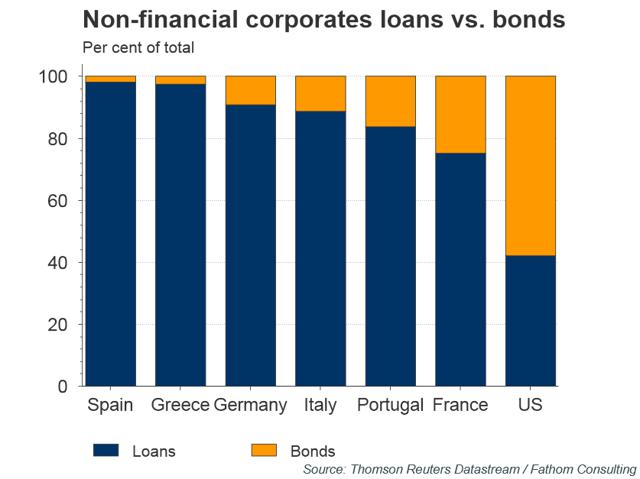

While a programme of corporate bond purchases might work well in a country with well-developed capital markets - such as the US, where the majority of the debt of non-financial firms is in the form of bonds - it stands a far smaller chance of success in the euro area. Non-financial firms in the euro area are far more reliant on banks. Across the region, bank debt accounts for some 90% of all non-financial corporate debt. In the periphery that figure is close to 100%

The main purpose of any asset purchase programme would surely be to give Frankfurt a means of creating more high-powered money, in turn forcing the exchange rate down and generating some upward pressure on inflation. But in our view only the sovereign bond market is large enough to achieve this objective. According to the ECB's Eurosystem Collateral Data, the amount of eligible corporate bonds, including those of financial corporations, is close to €1.4 trillion. At the same time, the "use of collateral" data for corporate bonds suggests that only 7% or €98 billion of these are actually employed as collateral - the corresponding percentage for ABS is 44%. However, the proportion of all eligible bonds that are senior rated is close to 40% of the €1.4 trillion figure - so roughly €560 billion. Considering that the ECB can buy only so much without distorting the market severely, then it becomes apparent that the corporate bond market is simply not large enough to allow the ECB to expand its balance sheet sufficiently.

QE buys time - it is not a solution in its own right

We have argued since the beginning of this year that the ECB will eventually have no option but to engage in a massive sovereign bond buying programme - despite the persistence of heavy political headwinds. The markets have moved closer to our view and - according to a Reuters poll - now assign a 50% probability to such a programme being launched. Like corporate bond purchases, QE would also work mainly through the exchange rate channel. Due to the far bigger size of the sovereign bond market, government bond purchases would put significant downward pressure on the euro. But even so, outright QE on its own would only buy time.

Even were the ECB to buy €1 trillion of sovereign debt from banks, this would not do enough to repair their balance sheets as they are labouring under a mountain of NPLs and are having to contend with ever tougher capital requirements. This week the Basel-based Financial Stability Board (FSB) announced that many of the 30 global, systemically-important banks - most of the ones in Europe - will have to find large amounts of capital to comply with new, tougher capital rules. What is more, even ignoring the banks' impaired ability to lend for the moment, the corporates and households that would borrow are labouring under their own debt overhang and trepidation over their future circumstances. As such, they are, understandably, reluctant to ask for loans in the first place.

The situation in Europe has all the hallmarks of a balance sheet recession. Hence, it should come as no surprise that a degree of balance sheet repair must take place before there are grounds for confidence in an improving outlook. QE would be a massive step forward - even if focused on Bunds, as is likely to be the case if Frankfurt chooses to base it off the ECB capital key. This would work chiefly through the exchange rate channel for the whole of the euro area, but would work to reflate the core countries specifically (something very desirable to ameliorate the imbalances within the common currency area) and be more politically palatable to Germany to boot.

QE is therefore a necessary condition for resolution, but not a sufficient one. It would remove a large part of the dross from European banks' balance sheets - namely periphery sovereign bonds - but will still leave them laden with plenty of NPLs stemming from NFC and household lending. To remove these, nothing short of a direct bank recapitalisation - allowing banks to write them off or offload them to a bad bank and then printing enough euros to cover the shortfalls - will do.

0 comments:

Publicar un comentario