Corporate saving in Asia

A $2.5 trillion problem

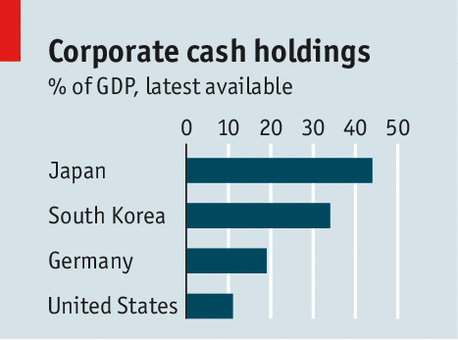

Japanese and South Korean firms are the world’s biggest cash-hoarders. This hurts their economies

Sep 27th 2014

.

THE odd thing about prudence is that too much of it can be deadly. Timid drivers crawling along a motorway create more risk than they avoid. Children who are over-protected from germs end up with weaker immune systems. Economies are the same: too much saving can lead to a loss of vigour or, as Keynes put it, to a “paradox of thrift”. That is why Japanese and South Korean firms, two of the world’s biggest hoarders, need to be cajoled into parting with their cash.

Corporate saving has risen across the rich world in recent years. Bosses have felt a greater need to protect themselves against financial turmoil. There have also been fewer opportunities for investment in ageing economies. But East Asia is an extreme case. Japanese firms hold ¥229 trillion ($2.1 trillion) in cash, a massive 44% of GDP. Their South Korean counterparts hold 459 trillion won ($440 billion) or 34% of GDP. That compares with cash holdings of 11% of GDP, or $1.9 trillion, in American firms. If East Asia’s firms spent even half of their huge cash hoards, they could boost global GDP by some 2%.

Sadly, that kind of largesse is unlikely. Bosses in East Asia are still scarred by bitter experience—in Japan’s case by the financial crash that began in the late 1980s, in South Korea’s by its collapse in 1997. In both countries, companies learned that banking relationships can sour overnight—a lesson reinforced by the crunch in 2008.

What makes sense for a timid boss does not always help his workers or investors. In South Korea, company earnings have grown faster than wages for more than a decade. In Japan wages fell 3.5% between 1990 and 2012, while prices rose by 5.5%. And shareholders should feel shortchanged, too. Japanese firms pay out less of their profits in dividends than any other country in the G7. The dividend yield on Korea’s KOSPI index is just 1.2%, the lowest of any big economy.

And East Asia’s economies have also suffered. If they had been paid more, Japanese consumers might have spent more. Korean households, struggling with rapidly-growing debt-burdens, have also been squeezed. And the chaebol’s hoarding also harms the country’s longstanding growth strategy—capital investment to support high-tech exports. Investment growth in South Korea has averaged just 1% since 2008.

Pay out and prosper

Mr Abe could certainly do more—for instance, forcing firms to have multiple independent directors (who make up 9% of Japanese boards, compared with around 70% of America’s). But his approach is wiser than South Korea’s attempt to micromanage firms. Why should Samsung build a factory at home if putting one in, say, Vietnam is more efficient? It would be better to strengthen outside shareholders, particularly in the family-run chaebol, and to open up its banking market.

So some solutions are misplaced, but the real scandal is the hoarding in the first place. The message to Japanese and Korean bosses is simple: if you don’t know what to do with the cash, give it back to shareholders. It is, after all, their money.

0 comments:

Publicar un comentario