The separation principle drives the Fed towards tapering

November 24, 2013 4:46 pm

by Gavyn Davies

The past week has been another important one for Fed watchers, a group which nowadays seems to include almost every active investor in the financial markets. Following the decision of the Senate on Thursday to ban filibustering on Presidential nominations to many important federal posts, it has been suggested by Morgan Stanley that Ms Yellen might take up her position as Chair in time for the next meeting of the FOMC on 17-18 December, two meetings earlier than previously expected.

Furthermore, according to Neil Irwin, President Obama will now find it easier to appoint at least two new monetary doves to support Ms Yellen on the Board of Governors next year. This will offset what might otherwise have been a shift towards hawkishness on the FOMC, since regional Presidents Fisher and Plosser (both hawks) are rotating into voting status, and the unannounced new President of the Cleveland Fed may turn out to be “on the hawkish end”, according to J.P. Morgan.

These personnel changes will create their own uncertainty. But, in addition, the Fed’s monetary strategy is clearly in a state of flux, with its approach to tapering having developed markedly in recent weeks. A new “separation principle” seems to be emerging, and it explains why the FOMC seems eager to begin winding down its asset purchases in the near future, while relying even more heavily than before on “lower for longer” guidance on forward short rates. This could have important ramifications for markets.

The perceptive Tim Duy’s Fed Watch provides strong evidence from the latest FOMC minutes that the committee is increasingly desperate to taper soon, even if there has not been a “substantial” improvement in the outlook for the labour market before they press the button. This is because a significant number of participants now sees the costs of asset purchases beginning to outweigh the benefits, in ways which have not been fully explained to the public. Tapering may not happen in December, but the precise timing no longer matters very much: it is just around the corner in any event.

The Separation Principle

The separation principle was spelled out more clearly than ever before in Ben Bernanke’s speech on communications policy last Tuesday, a speech which is in many ways a fitting swan song for his time as Chairman. This also gives a better reason for the Fed’s surprising decision not to taper at its September meeting than has previously been aired in public.

Mr Bernanke’s core point is that the Fed’s reading of monetary conditions now distinguishes sharply between two distinct factors, which are the expected forward path for short rates, and the term premium built into long term bond yields [1]. Asset purchases by the central bank are intended to affect the second of these factors, the term premium, but are not intended to give any signal to the markets about the Fed’s willingness to keep short rates at zero for a prolonged period ahead. If the markets incorrectly make such a connection (as the FOMC minutes accept may have happened during the summer), this is not welcome for the Fed, and it needs to be corrected by more explicit forward guidance.

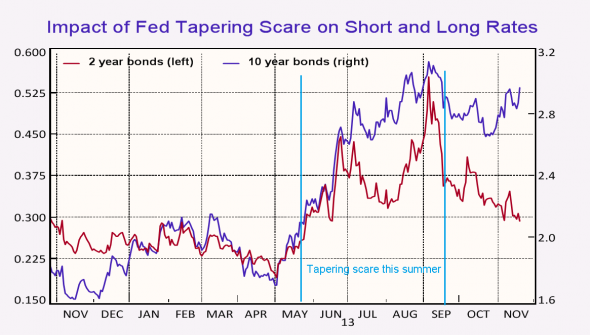

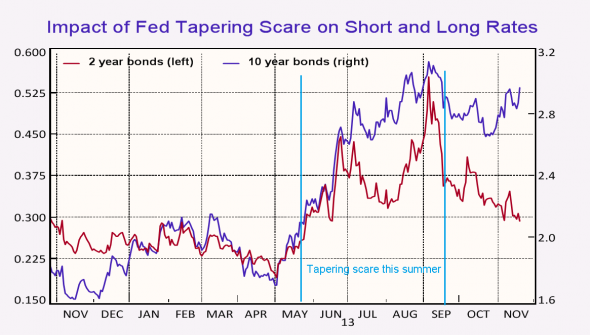

The graph below gives some indication of what the Fed disliked about the markets’ reaction to its own tapering talk between May and September this year:

The key feature of the tapering scare was that the term premium and the forward path for short rates (proxied here by the two year treasury yield) both rose simultaneously after the FOMC minutes on 22 May, which suggested that tapering was probable within the next few meetings. Mr Bernanke has now said explicitly that the part of the increase in bond yields that was due to the rise in forward short rates was not desired by the Fed. This was obviously a major factor in their shock decision to postpone tapering at the September meeting.

Importantly, the latest tapering scare, from late October onwards, has not seen any rise in forward short rates, which have in fact continued to drift downwards. The fact that the market is now paying attention to the separation principle will please the FOMC, and will make it far more likely that they will begin to taper within the next two or three meetings.

The separation principle implies that the Fed is now comfortable with increases in bond yields driven by the term premium, and is similarly happy with a sharply upward sloping yield curve. Given that they have spent much of the past five years trying to reduce the term premium, and flatten the yield curve, this is an unexpected turn of events. Why have they changed their thinking?

According to Mr Bernanke, they are far less certain about the impact of a reduced term premium than they are about a lower-for-longer path for short rates. The greater the uncertainty attached to a policy weapon, the less it should be used (according to the Brainard principle explained in this earlier blog). But there is more to it than that.

Some members of the FOMC seem to have decided that asset purchases are less effective in stimulating economic activity than the same dose of monetary easing delivered by lower-for-longer short rates. This conclusion follows from a research paper published a year ago by the Fed’s Michael Kiley [2], which argued the following:

Furthermore, Fed Governor Jeremy Stein has argued that asset purchases might well cause more distortions to asset prices via the reach for yield than the distortions which are caused by lower short rates. With the benefits of asset purchases in terms of economic activity being less, and the costs in terms of market bubbles being greater, it is not surprising that the Fed is opting increasingly for the forward short rate weapon.

In summary, there is no evidence that the Bernanke Fed has lost its enthusiasm for its overall dovish stance in its final phase. Far from it. But it increasingly favours a mix that deliver its monetary stimulus through a channel that affects risk assets less dramatically than it has before [3]. If Janet Yellen agrees, the next phase of its monetary stimulus may be less unambiguously friendly for equities and other risk assets than quantitative easing has been up to now.

————————————————————————————

Footnote

[1] The term premium is that part of the bond yield that is not explained by the forward path for short rates. See Ben Bernanke here.

[2] I am indebted to Michael Feroli of J.P. Morgan for reminding his readers about this.

[3] Paul Krugman and Simon Wren Lewis point out that the Swedish central bank, the Riksbank, reacted to asset price bubbles (in their case housing) by raising short rates, despite the fact that inflation was well below target. The Fed may be trying to avoid this dilemma by changing the mix of monetary policy between asset purchases and forward guidance.

Furthermore, according to Neil Irwin, President Obama will now find it easier to appoint at least two new monetary doves to support Ms Yellen on the Board of Governors next year. This will offset what might otherwise have been a shift towards hawkishness on the FOMC, since regional Presidents Fisher and Plosser (both hawks) are rotating into voting status, and the unannounced new President of the Cleveland Fed may turn out to be “on the hawkish end”, according to J.P. Morgan.

These personnel changes will create their own uncertainty. But, in addition, the Fed’s monetary strategy is clearly in a state of flux, with its approach to tapering having developed markedly in recent weeks. A new “separation principle” seems to be emerging, and it explains why the FOMC seems eager to begin winding down its asset purchases in the near future, while relying even more heavily than before on “lower for longer” guidance on forward short rates. This could have important ramifications for markets.

The perceptive Tim Duy’s Fed Watch provides strong evidence from the latest FOMC minutes that the committee is increasingly desperate to taper soon, even if there has not been a “substantial” improvement in the outlook for the labour market before they press the button. This is because a significant number of participants now sees the costs of asset purchases beginning to outweigh the benefits, in ways which have not been fully explained to the public. Tapering may not happen in December, but the precise timing no longer matters very much: it is just around the corner in any event.

The Separation Principle

The separation principle was spelled out more clearly than ever before in Ben Bernanke’s speech on communications policy last Tuesday, a speech which is in many ways a fitting swan song for his time as Chairman. This also gives a better reason for the Fed’s surprising decision not to taper at its September meeting than has previously been aired in public.

Mr Bernanke’s core point is that the Fed’s reading of monetary conditions now distinguishes sharply between two distinct factors, which are the expected forward path for short rates, and the term premium built into long term bond yields [1]. Asset purchases by the central bank are intended to affect the second of these factors, the term premium, but are not intended to give any signal to the markets about the Fed’s willingness to keep short rates at zero for a prolonged period ahead. If the markets incorrectly make such a connection (as the FOMC minutes accept may have happened during the summer), this is not welcome for the Fed, and it needs to be corrected by more explicit forward guidance.

The graph below gives some indication of what the Fed disliked about the markets’ reaction to its own tapering talk between May and September this year:

The key feature of the tapering scare was that the term premium and the forward path for short rates (proxied here by the two year treasury yield) both rose simultaneously after the FOMC minutes on 22 May, which suggested that tapering was probable within the next few meetings. Mr Bernanke has now said explicitly that the part of the increase in bond yields that was due to the rise in forward short rates was not desired by the Fed. This was obviously a major factor in their shock decision to postpone tapering at the September meeting.

Importantly, the latest tapering scare, from late October onwards, has not seen any rise in forward short rates, which have in fact continued to drift downwards. The fact that the market is now paying attention to the separation principle will please the FOMC, and will make it far more likely that they will begin to taper within the next two or three meetings.

The separation principle implies that the Fed is now comfortable with increases in bond yields driven by the term premium, and is similarly happy with a sharply upward sloping yield curve. Given that they have spent much of the past five years trying to reduce the term premium, and flatten the yield curve, this is an unexpected turn of events. Why have they changed their thinking?

According to Mr Bernanke, they are far less certain about the impact of a reduced term premium than they are about a lower-for-longer path for short rates. The greater the uncertainty attached to a policy weapon, the less it should be used (according to the Brainard principle explained in this earlier blog). But there is more to it than that.

Some members of the FOMC seem to have decided that asset purchases are less effective in stimulating economic activity than the same dose of monetary easing delivered by lower-for-longer short rates. This conclusion follows from a research paper published a year ago by the Fed’s Michael Kiley [2], which argued the following:

The results indicate that the short-term interest rate has a larger influence on economic activity, through its impact on the entire term structure, than term and risk premiums (for equal-sized movements in long-term interest rates)… A sustained decline in long-term interest rates brought about by a decline in the term premium has about half the effect of a similar decline in long-term interest rates brought about through a decline in short-term interest rates.

Furthermore, Fed Governor Jeremy Stein has argued that asset purchases might well cause more distortions to asset prices via the reach for yield than the distortions which are caused by lower short rates. With the benefits of asset purchases in terms of economic activity being less, and the costs in terms of market bubbles being greater, it is not surprising that the Fed is opting increasingly for the forward short rate weapon.

In summary, there is no evidence that the Bernanke Fed has lost its enthusiasm for its overall dovish stance in its final phase. Far from it. But it increasingly favours a mix that deliver its monetary stimulus through a channel that affects risk assets less dramatically than it has before [3]. If Janet Yellen agrees, the next phase of its monetary stimulus may be less unambiguously friendly for equities and other risk assets than quantitative easing has been up to now.

————————————————————————————

Footnote

[1] The term premium is that part of the bond yield that is not explained by the forward path for short rates. See Ben Bernanke here.

[2] I am indebted to Michael Feroli of J.P. Morgan for reminding his readers about this.

[3] Paul Krugman and Simon Wren Lewis point out that the Swedish central bank, the Riksbank, reacted to asset price bubbles (in their case housing) by raising short rates, despite the fact that inflation was well below target. The Fed may be trying to avoid this dilemma by changing the mix of monetary policy between asset purchases and forward guidance.

0 comments:

Publicar un comentario