The implications of secular stagnation

November 17, 2013 4:00 pm

by Gavyn Davies

One week ago at the IMF Research Conference, Larry Summers delivered a remarkable speech about secular stagnation, which he suggested might be the defining issue of our age. The term secular stagnation, coined by American Keynesian Alvin Hansen in the late 1930s, has always had a polarising effect among economists, and the same will certainly be true again this time. But whatever one thinks about the argument, the Summers speech, at 16 minutes long, is a tour de force that demands to be watched.

Paul Krugman has also weighed in powerfully, both before the Summers speech here, and after it here. In a nutshell, the argument is that the equilibrium real rate of interest in the global economy has been significantly negative (around -2 to -3 per cent) since at least the mid 2000s, while the actual real rate (at least on bonds) has consistently been much higher than this, despite the efforts of the central banks to reduce it [1].

The alleged consequence of the fact that the actual real rate is above the equilibrium is that there has been a prolonged period of under-investment in the developed economies, with GDP falling further and further behind its underlying long run potential. In a largely unsuccessful effort to close the gap, the central banks have created asset price bubbles (technology stocks in the late 1990s, housing in the mid 2000s and possibly credit today), since this has been the only means available to boost demand.

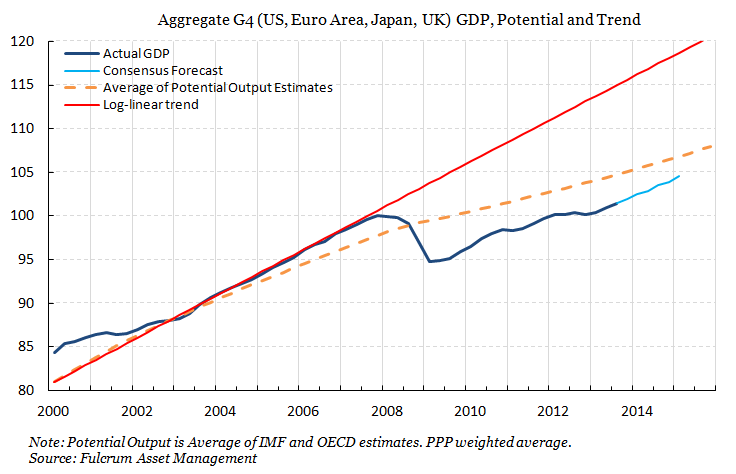

The latest evidence on secular stagnation is reflected in the graph below:

The blue line is actual GDP for the major four developed economies, which has only recently exceeded the last peak in 2007 by a couple of percentage points. Not only has GDP stagnated in absolute terms, it has of course fallen about 13 per cent below the long term extrapolated trendline, shown in red.

This huge gap has led economists at the OECD and IMF to suggest that potential output has not actually followed the red line, but has instead followed a path sketched by the dotted orange line, reflecting the damage done to the capital stock and the effective supply of labour by the recession.

Few economists dispute that the actual level of GDP is still below the orange dotted line, which unfortunately cannot be directly observed. This is the case for keeping monetary policy aggressively easy, as long as policy makers believe that asset prices are not in bubble territory (something which Janet Yellen confirmed last week).

But recently, the major central banks have published research that goes further than this, arguing that potential output might be increased towards the red line if the “right” policies are followed. A paper at the IMF conference by the Fed’s David Wilcox argues that demand might create its own supply by boosting capital investment and raising labour participation. The Bank of England expects that UK productivity will rebound as the economy expands.

Even the ECB published a paper last week which argued that the very low rates of growth in potential GDP (only 0.5 per cent per annum!) could be improved if structural reforms were accelerated. Note that unlike the Fed and the BoE, the ECB does not argue that the central bank should be boosting demand to raise potential output; crucially, they see it as a supply side issue, while others are blurring these distinctions.

So what do the secular stagnationists add to these debates?

Implications of Secular Stagnation

The first implication, if they are right, is that the problem of under-performance of GDP will last for a very long time, and will not solve itself through flexibility in prices and interest rates, which is what happens in classical economic models (rapidly), and in new Keynesian models (more slowly). The reason for this is presumably that the zero lower bound prevents nominal interest rates from falling, and also prevents prices and wages from adjusting downwards. Therefore none of the normal forces for restoring equilibrium apply.

A second implication is that the normal route through which monetary policy works, by bringing forward consumption from the future into the present, is unlikely to be successful [2]. If the secular stagnationists are right, there will still be a shortage of demand when the future comes around, so there will be a need for ever-greater injections of monetary stimulus (presumably through quantitative easing) in order to avoid an ever-worsening recession.

Sir Mervyn King pointed this out shortly before he retired from the BoE, but few people paid much attention. Sooner or later, central bankers are bound to become concerned about asset bubbles (rightly), or the risk of losses on their bond holdings, and give up this path. The consequences for asset prices could be very painful when this happens, not because the asset purchases themselves are crucial, but because the markets might decide that there is no other means of keeping growth going.

A third implication is that calls for fiscal action are bound to intensify. Following the Summers speech, Ben Bernanke commented that secular stagnation was unlikely to occur, because there would always be capital projects with a positive rate of return that would be undertaken by the public sector. These projects could be financed by raising public debt at zero or negative real rates of interest, so the debt would be sustainable and the net worth of the government would actually improve. Therefore, in a rational world, public investment would always be used to end the secular stagnation.

This, apparently, had first been pointed out by Paul Samuelson in the debates which followed the 1930s Depression [3], and the conclusion about public investment now seems to be supported by most shades of professional economic opinion, including Ken Rogoff at the IMF conference. Yet there is little sign of it happening on any significant scale.

Conclusion

With wage and price inflation continuing to hover close to zero, and with global bond yields still so low, the secular stagnationists currently appear to be having the better of the debate. But, of course, there is a counter case.

They may not be right that real GDP can return to the long term (red) trendline, or even the more pessimistic potential output (orange) line. Attempts to get there would then be followed not only by asset bubbles, but also by rising inflation, and then a massive economic correction.

Concerns about these risks appear to be winning the argument on the fiscal side, which is still tightening by a little under one percentage point of GDP per annum in the developed world. They also hold sway in much of the ECB Governing Council. But the Fed, the BoE and the BoJ seem to be leaning in the other direction [4].

Essentially, this comes down to the oldest macro-economic question of all: where do policy makers want to take risks, with higher inflation or lost output and employment?

Paul Samuelson, once said that “good questions outrank easy answers”. His nephew, Larry Summers, has certainly asked a very good question on this occasion.

————————————————————————————-

Footnotes

[1] The exact causes of the drop in the equilibrium real rate are not fully agreed. Larry Summers points to the global savings glut, and the technology revolution. Paul Krugman favours the decline in investment and consumer demand after the financial crash, and also mentions declining population growth. Both believe that the causes will not disappear soon.

[2] A decline in the real rate of interest reduces the incentive to save and therefore increases consumption today, while reducing consumption at later dates. If consumption today is temporarily reduced by a recession, then lowering the real rate of interest will stabilise cyclical fluctuations in the economy.

[3] Samuelson said that the government could always level out a hill so that the railroad could operate more efficiently.

[4] Russell Jones and John Llewellyn at the excellent Llewellyn Consulting reach the following worrying conclusions: “OECD economic growth will continue to disappoint by pre-crash standards, especially in Europe. Enduring excess capacity and depressed inflation expectations will combine to keep actual inflation historically low, if not put the price level under downward pressure. Unorthodox monetary policies will increasingly come to be judged as producing diminishing returns where output is concerned, while generating burgeoning risks to financial stability. Policymakers will meanwhile resist calls for a major fiscal u-turn until it becomes socially and politically unavoidable, or another negative shock forces them into it.

0 comments:

Publicar un comentario