The Sum Of All Money Market Fears

Oct 8 2013, 12:29

Reforms proposed by the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) threaten money market funds and short-term, commercial paper rates -- even for companies with excellent credit ratings.

General Electric (GE), Coca Cola (KO), JPMorgan Chase (JPM), State Street (STT) and Wells Fargo (WFC) depend on money market funds for cheap, short-term financing. Banks mentioned rank among the largest money market fund operators and face a potential double whammy if the proposed reforms are implemented.

The success of money market funds

Rapid inflation and high interest rates of the 1970s and early 1980s left banks in a tough spot. Regulation Q prevented their payment of interest on demand deposits (i.e. checking accounts) and so banks offered money market funds paying dividends.

By early 1983, money market funds were experiencing net cash outflows. In July 1983, however, the SEC revised the accounting rules governing money market funds to provide them with a stable net asset value. The cash then poured into money market funds as never before.

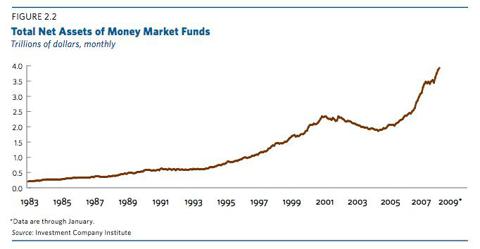

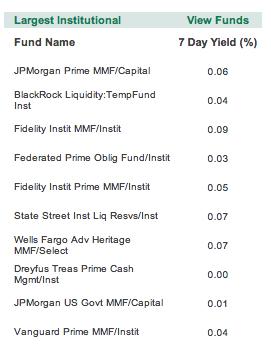

"Since that rule [Rule 2a-7] was adopted, money market fund assets have grown from about $180 billion to $3.9 trillion as of January 2009," according to the Investment Company Institute.

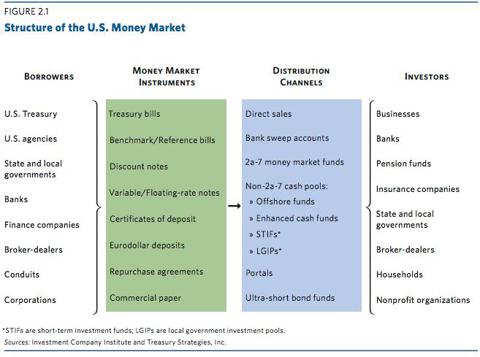

(click to enlarge) Even as the restriction on banks paying interest on demand deposits loosened, interest rates on traditional bank products remained low. The reason: Money market funds helped banks to skirt "reserve requirements and capital rules that would apply if the bank took deposits and made loans." The "shadow banking system" this created made some banks "too big to fail."

Even as the restriction on banks paying interest on demand deposits loosened, interest rates on traditional bank products remained low. The reason: Money market funds helped banks to skirt "reserve requirements and capital rules that would apply if the bank took deposits and made loans." The "shadow banking system" this created made some banks "too big to fail."

Even as the restriction on banks paying interest on demand deposits loosened, interest rates on traditional bank products remained low. The reason: Money market funds helped banks to skirt "reserve requirements and capital rules that would apply if the bank took deposits and made loans." The "shadow banking system" this created made some banks "too big to fail."

Even as the restriction on banks paying interest on demand deposits loosened, interest rates on traditional bank products remained low. The reason: Money market funds helped banks to skirt "reserve requirements and capital rules that would apply if the bank took deposits and made loans." The "shadow banking system" this created made some banks "too big to fail."

The SEC's "Indecent Proposal"

The SEC's proposed money market reform would turn back time and make money market funds much as they were when net asset values still floated. Among the proposed changes are restrictions on withdrawing money during times of market stress and a requirement for floating net asset values.

State Street summarized the proposed reforms in a September letter to the SEC.

"The first ("Alternative 1") would require all prime, institutional funds to operate with a floating net asset value ("NAV"). The second ("Alternative 2") would, at board discretion, impose a system of redemption fees and gates on all prime funds in times of market stress. The Commission suggests a final rule could include either, or both, of these suggested alternatives,..."

The sum of all corporate fears

If these reforms were enacted, the size of the money market industry would shrink and JPMorgan Chase, State Street, Wells Fargo and major industrials including General Electric and Coca-Cola would pay much more on short-term commercial paper purchased by money market funds. (Money market funds purchase 40% of short-term commercial paper.)

For example, the prime rate in summer 2012 was 3.15% versus the 6 month commercial paper rate, which was 0.24%. Had JPMorgan Chase, State Street, Wells Fargo, General Electric and Coca-Cola been forced to pay the prime rate on their collective short-term commercial paper held by money market funds, they would have paid $2.7 billion in interest as compared to $206 million.

In the circular announcing the proposed money market reforms, the SEC actually said money market demand for commercial paper could erode away:

"Because prime money market funds' holdings are large and their investment strategies differ from some investment alternatives, a shift by investors from prime money market funds to investment alternatives could affect the markets for short-term securities."

Banks have an even more serious addiction

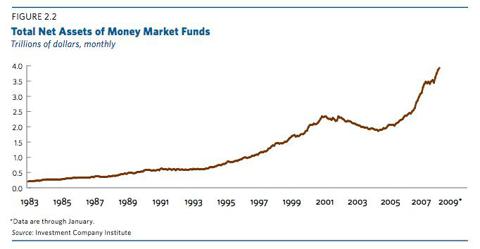

According to 2013 asset rankings, JPMorgan Chase, State Street and Wells Fargo were among the largest operators of institutional money market funds. (See chart at right.) These same banks were also among the top 50, non-government issuers of corporate debt held in the universe of all money market fund portfolios in 2012. (See chart above.) Were this short-term financing to disappear, global banks and financial institutions would find themselves in a world of hurt.

In June 2012 testimony before the Senate Committee on Banking, Housing, and Urban Affairs, Harvard Business School Professor David S. Scharfstein estimated global financial institutions such Bank of America (BAC), Citigroup (C), Goldman Sachs, JPMorgan Chase, Morgan Stanley (MS) and Wells Fargo relied on money market funds for 25% of their short-term, wholesale funding. However, in April 2013, Scharfstein raised the estimate 10 percentage points to 35%.

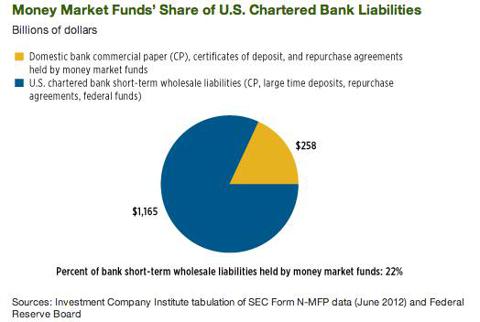

The Investment Company Institute estimates that in 2012 prime money market funds accounted for 22% or roughly $258 billion of the short-term liabilities of major banks. (See chart above.)

The money market tsunami

JPMorgan Chase, State Street and Wells Fargo worry the proposed floating net asset value would destroy the money market business for them.

In a September 2013 comment letter to the SEC, State Street wrote in support of the status quo.

". . . we believe that a stable $1.00 per share NAV is the fundamental characteristic of money market funds, and if money market funds were unable to provide that stable NAV, investors would transition their cash investments to other vehicles and threaten the viability of money market funds as an investment option."

JPMorgan Chase struck a similar chord:

"Many of these investors, based on their organizations' objectives and investment guidelines, will not consider investing in a MMF with a floating NAV."

Wells Fargo cautioned:

"A variable NAV requirement would likely have a significant negative impact on investors. Some investors, including corporate liquidity managers, municipalities and trustees, may face hurdles, such as governing investment guidelines, that may prevent them from investing in anything but a stable value money market fund." (Note:The quote is from the company's 2009 letter, which it included by reference in its 2013 letter to the SEC on the same subject.)

Federated Investors' (FII) legal counsel wrote the SEC on the proposed reforms with cost concerns.

"Federated estimates that the initial nationwide costs of implementing a floating NAV would be in the range of at least $4 billion to $7 billion."

State Street echoed the concern:

"In the absence of extremely costly (probably cost-prohibitive) system enhancements, we are concerned that adoption of this Alternative [to require a floating NAV) will significantly limit the utility of money market mutual funds as short-term investment vehicles for a broad range of institutional investors."

The IRS concern

Most financial firms are concerned over what the unresolved tax implications shifting to a floating net asset value could mean. The Internal Revenue Service has held preliminary discussions with the SEC on the idea of exempting money market funds from capital gains, but nothing as of yet has been decided. Were money market fund investors forced to account for all their gains and losses, it would be a monumental accounting assignment far greater than the benefit of the increased yield provided by money market funds.

There is still time to act

The SEC could render a decision on money market fund reform later this year. If the decision is to impose floating net asset values, it would be a devastating blow to money market funds.

0 comments:

Publicar un comentario